A Behavioural Insights Analysis of the Effects of Environmental, Social, and Governance Factor (ESG) Disclosure and Advertising by Investment Funds on Retail Investors

Executive Summary

Executive Summary

Incorporating environmental, social, governance (ESG) factors into investment decision-making has become a key issue for capital markets and investor protection. This is marked by a number of factors including growth in assets under management of ESG investment funds, demands for ESG information when making investment decisions, and pressing sustainability objectives in the global economy. Notably, there has been rapid growth, followed by continued net inflows into ESG investment funds in Canada in the past few years.[1] However, these inflows bring challenges that may undermine investor protection and confidence in capital markets, such as greenwashing. Thus, it is imperative for regulators to examine the retail investor experience with respect to investing in ESG investment funds in order to further the mandate of investor protection.

Based on our review, we have noted that it is challenging for retail investors to evaluate the ESG component of investment funds for several reasons including:

- Lack of standardized definitions of ESG factors

- Lack of standardized methodologies to measure ESG factors

- Lack of a definition of sustainability

- Differences in ratings and rankings variables, and their understandability

- Different values, beliefs, and motivations within retail investing

- Behavioural challenges when investing

Disclosure related issues and the key concern of “greenwashing” have led securities regulators and international organizations to address these ongoing challenges. The International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) publication in June 2023 of their first two sustainability disclosure standards (S1 & S2) is an important milestone for the development of a global framework for sustainability disclosure. However, IFRS S1 and S2 will not enter into effect in Canada until given effect, with or without modifications, by the Canadian Sustainability Board, and then action is taken by the Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA) to establish disclosure rules in Canada.

In this report, we examine greenwashing in investment funds, which occurs when a fund’s disclosure or marketing intentionally or inadvertently misleads investors about the ESG-related aspects of the fund.[2] We also explore the retail investor experience in relation to ESG investment funds by examining their motivations and behaviours.

ESG Foundations

ESG refers to a collection of non-financial factors used to assess an organization or investment's practices and performance on various sustainability and ethical issues. Investors can consider ESG factors when investing, which can include identification of material risks, growth opportunities, and other normative goals. Despite no globally agreed upon taxonomy, ESG can be understood as:

- Environmental: Issues relating to the quality and functioning of the natural environment and natural systems. This includes, but are not limited to, climate change, biodiversity, air and water pollution and natural resource management.

- Social: Issues relating to the rights, well-being and interests of people and communities. This includes, but are not limited to, reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples, diversity and inclusion, data privacy and security, labour practices, supply chain management and human rights.

- Governance: Issues relating to the governance of underlying companies and other investee entities. This includes, but are not limited to, board structure and independence, business ethics, executive compensation, and shareholder rights.

When retail investors make decisions to invest in ESG products, their selection of a fund may be influenced by the presence of ESG ratings or an ESG-related name. There are several organizations that provide quantitative measures to review ESG performance of companies. However, there is no standardized measurement of ESG factors. The volume of different types of ratings and rankings, their level of transparency, understandability, governance, and inconsistent terminology, have created challenges for stakeholders to navigate the ESG space.

ESG ratings and the data produced by ratings agencies can be one of several sources of information used by fund managers to develop ESG investment funds. The ratings generally use an approach that assesses the sustainability-related financial risks and opportunities to the company rather than measuring a company’s impact on the environment and/or society. These concepts are known as enterprise value vs impact value. These different frameworks may be misunderstood by retail investors and other users of ESG data and ESG ratings. For example, retail investors may review the ESG ratings for the company and assume an ESG rating is based on the company’s low carbon footprint (impact-value) when, in actuality, the rating reflects the company’s low risk exposure to climate change events (enterprise-value).

ESG products are built using financial, enterprise-value, and impact-value reporting, ESG ratings, and proprietary research. A spectrum of approaches is possible—from enterprise-value focused to impact-value focused—with many variances in between. There are five approaches commonly used to build ESG products: ESG integration, exclusionary screening, inclusionary screening, impact, and active (see Table i for descriptions of these approaches).

Table i: Spectrum of ESG investment themes

Objective | Integration Themes | Description |

Enterprise- value focused Image

Impact-value focused | ESG Integration | Incorporates ESG data, alongside traditional financial analysis, into the securities election process. |

| Exclusionary Screening | Exclusionary screens can often be categorized as either values-based or norms-based. Excludes, from the investment universe, companies, sectors, or countries involved in activities that do not align with the moral values of investors or with global standards. | |

| Inclusionary Screening | Tilts portfolio toward one of following:

| |

| Impact | Targets a measurable positive social and/or environmental impact. Investments are generally project specific and tend not to leverage ESG ratings. | |

| Active (i.e., corporate engagement and stakeholder action) | Entails engaging with companies and voting company shares on a variety of ESG issues to initiate changes in behaviour or in company policies and practices. |

Source: CFA, PRI, State Street

Marketing of ESG Investment Funds

Fund managers use several vehicles to market products and provide information to retail investors. Typically, the following four channels are used:

- Push marketing (direct-to-consumer advertising) and press releases

- Product names and product labels

- Websites and retail outreach channels: fund manager and product branding/websites

- Fund documentation: prospectus, Fund Facts, fund factsheets, annual reports

Within these marketing vehicles, greenwashing is of serious concern. Greenwashing—defined by the CSA—occurs when a fund’s disclosure or marketing intentionally or inadvertently misleads investors about the ESG-related aspects of the fund.[4] The CSA Staff Notice 81-334 provided guidance to investment funds and their investment fund managers to “enhance the ESG-related aspects of the funds’ regulatory disclosure documents and ensure that the sales communications of such funds are not untrue or misleading and are consistent with the funds’ regulatory offering document.” The notice also states that “the name and investment objectives of a fund should accurately reflect the extent to which the fund is focused on ESG, where applicable, including the particular aspect(s) of ESG that the fund is focused on.”[5] In June 2024, new provisions were added to Canada’s Competition Act that explicitly target greenwashing, which require businesses to have testing or substantiation to support certain environmental claims.[6]

The inherent complexity of ESG information makes it challenging to test and validate claims made by fund managers. Thus, regardless of whether intentional or unintentional, ESG marketing claims have the risk of misleading retail investors.

ESG Investment Funds and Retail Investors

Our examination of the retail investor experience finds that retail investors' beliefs and attitudes towards ESG significantly influence their investment decisions when deciding to invest in funds. Depending on their beliefs and attitudes, retail investors may fall anywhere along the continuum between being financially-driven and values-driven. Financially-driven investors focus on reducing risks and increasing returns, while values-driven investors aim to create ESG-focused changes. Consequently, values-driven investors may accept lower returns and higher fees for investment funds with higher ESG ratings.

When deciding to invest in ESG investment funds, investors may examine product names, ESG ratings, and marketing materials. Product names can significantly influence decisions, as many retail investors may not look too far beyond them. Retail investors in ESG investment funds may have biases and use heuristics (i.e., mental shortcuts), leading them to rely on ESG ratings. Values-driven investors, in particular, may make investing decisions based on positive emotions rather than rational metrics.

A consideration of the mental shortcuts that people take such as biases and heuristics when designing policy or educational interventions can improve ESG investing decisions. Retail investors should strive to understand their own motivations, recognize the volume and quality of information, and be cautious of marketing tactics. Financial advisors play a crucial role in guiding retail investors through ESG investing by leveraging their financial literacy and product knowledge, though they may face similar challenges with complex ESG information. Supporting and strengthening advisors' proficiency in ESG knowledge is recommended to better support investors and navigate the ESG landscape effectively.[7]

The Experiment

The literature review on ESG retail investing was complemented by an experiment to examine retail investors’ attitudes, values, and intentions towards ESG investment funds. The purpose of this rigorous experiment is to support OSC in facilitating data-driven, evidence-based regulation. We used an experimental method known as a discrete choice experiment (DCE)—a scientifically robust technique that is used to understand individual preferences by presenting them with sets of hypothetical choices.

In our experiment, we asked participants to choose between two investment funds—with each choice having a total of 8 attributes displayed within a key fact sheet (See Table ii for description of attributes). Both choices include the same attributes, however, their levels (i.e., versions of the attributes) may differ, as they are randomly selected from a predetermined list. For example, while both choices will have a fund name, the names may differ, such as ESG Equity Fund or Sustainable Equity Fund. By examining participants’ choices, we can determine which attributes within an ESG investment fund drive the selection of ESG investment funds.

Table ii: The attributes included in our key fact sheet.

Attribute | Description |

| Fund Names | Draw attention to and/or build associations about the purported activities, strategies, or impacts of the fund. |

| Investment Strategies | Articulate to participants how the fund will be invested to meet its stated objectives. |

| ESG Ratings | Reflect assessments of a fund's exposure to ESG-related risk vis-a-vis the portfolio's holdings. Ratings were either represented visually (out of 5 stars), or with letters grades. We also presented some funds with no ratings as a comparison. |

| Rating Explanations | Include information about the meaning of the ESG rating. |

| Investment Objectives | Clarify the goals of the fund. |

| Risk Profiles | Indicate the volatility of the fund and is based on how much the fund’s returns have changed from year to year considering its holdings. |

| Past Performance | Provide historical data on fund returns. |

| Management Expense Ratios (MERs) | The total of the fund’s management fee (which includes any trailing commission) and its operating expenses. |

A total of 961 retail investors participated in the experiment. Each participant was given a series of 12 choices between two key fact sheets with randomly selected levels of attributes and was asked to select which of the two funds they preferred. Following the experiment, participants completed a questionnaire on their attitudes towards investing and financial product ownership, and a demographic questionnaire.

Key Findings

- The ESG rating stood out as one of the most important attributes influencing consumer choice—second only to a fund’s past performance.

- The strength and format of the rating (letter grade and number of stars) were both impactful attributes.

- Higher ESG ratings had more positive influence on fund selection than lower ESG ratings.

- Star-rated funds had more positive influence on fund selection than letter-rated funds.

- The absence of an ESG rating was preferred to some of the lower ESG ratings, suggesting that there is a threshold at which ESG ratings transition from a motivating factor to a deterrent.

- Clustering—a data analysis method that organizes data into groups based on similarities—revealed two distinct segments of Canadian retail investors:

- Both segments were similar in their demographics and in their assessment of fund name, past performance, fund objective, and risk profile. They differed in their valuations of fund investment strategies, ESG ratings, rating explanations, and MER.

Values-Driven Investors | Financially-Driven Investors |

|

|

- Participants were not sensitive to mismatches between a fund’s more salient attributes (e.g., fund name) and its actual investment strategy. For example, participants were not sensitive to a misalignment in attributes such as fund name, “ESG Fund”, with the investment strategy “no ESG strategy”. This result suggests that Canadian retail investors may face risk from greenwashing of products available in the market.

The lack of standardization in ESG definitions and ratings is a critical issue that can lead to inadvertent and deliberate greenwashing. Even without deliberate greenwashing, ESG ratings can mislead retail investors, who believe they are investing in impactful companies aligned with their ESG values, when in fact they are often investing in ESG risks. It is unlikely that retail investors fully understand ESG ratings, yet these ratings are a particularly important factor when selecting ESG investment funds. The different types of ratings and lack of clarity around ratings allow manufacturers of these funds to potentially exploit investors’ tendency to rely on ESG ratings. Values-driven investors are particularly affected, as they are more willing to sacrifice returns, including higher MERs and potentially lower performance, to support funds they believe are making a positive impact. Based on these findings the OSC’s Research and Behavioural Insights Team recommends that stakeholders including authorities should incorporate the following to combat these challenges:

- Strive towards Clarity in ESG Definitions and Ratings

- Clarity around or potential standardization of ESG ratings to eliminate confusion and prevent greenwashing. This will support ESG ratings that are consistent and comparable across different funds and products.

- Educate Investors

- Improve retail investors’ understanding of ESG investing through education and outreach, including the differences between ESG risks and impacts, as well as being able to identify signs of greenwashing. This will empower investors to make decisions that truly align with their values.

- Strengthen Advisor Proficiency

- Promote financial advisors training on ESG investing to better support their clients.

These findings are crucial as they help the OSC and stakeholders understand the influence of ESG factors on retail investment decision-making and behaviour, including susceptibility to greenwashing. Recognizing the diversity in retail investors’ preferences and behaviours is a key element in supporting informed decision-making.

[1] Morningstar (2024). Canadian Investors Stuck with ESG in 2023.

[2] Canadian Securities Administrators. (2022; revised 2024). CSA Staff Notice - 81-334 - ESG-Related Investment Fund Disclosure.

[3] This can often be treated as a separate strategy.

[4] Canadian Securities Administrators (2022; revised 2024). CSA Staff Notice - 81-334 - ESG-Related Investment Fund Disclosure.

[5] Canadian Securities Administrators (2022; revised 2024). CSA Staff Notice - 81-334 - ESG-Related Investment Fund Disclosure.

[6] Competition Bureau Canada (2024). Public consultation on Competition Act’s new greenwashing provisions.

[7] The Client Focused Reforms changes to Know-Your-Product (KYP) requirements require registered firms to assess and individuals to understand the relevant aspects of the securities that they are considering making available to clients. Firms are expected to have the appropriate skills and experience to perform the necessary assessment of all securities to be made available to clients. Additional training and/or proficiency requirements are necessary for their registered individuals to understand ESG securities and make appropriate suitability determinations. Please refer to National Instrument 31-103 and Companion Policy 31-103CP for additional details.

National Instrument 31-103 Registration Requirements, Exemptions and Ongoing Registrant Obligations and Companion Policy to NI 31-103 CP Registration Requirements, Exemptions and Ongoing Registrant Obligations

Overview

Overview

Environmental, social, governance (ESG) factors have become increasingly prominent within retail investing. There has been rapid growth, followed by continued net inflows into ESG investment funds in Canada in the past few years.[8] Consequently, it is imperative for regulators to examine the retail investor experience with respect to investing in ESG investment funds to further the mandate of investor protection.

In this research report, the Ontario Securities Commission seeks to better understand ESG factors within retail investing and their influence on retail investing behaviours. The goal of the research report is to provide a review of:[9]

- The definitions, measurements, and disclosures of ESG

- How fund companies integrate ESG into their products and marketing

- How retail investors approach the multi-dimensional nature of ESG investment funds when making investing decisions including assessing a product’s sustainability and performance

- The influence of ESG factors on retail investment decision making and behaviour

Report Structure

Prepared by the OSC, this report provides a high-level summary of key information contained within two reports resulting from our collaboration with PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) and The Decision Lab (TDL), respectively. This report contains a literature review and environmental scan on ESG and retail investing that was prepared by PwC in collaboration with OSC, and a behavioural science experiment also on ESG and retail investing that was prepared by TDL in collaboration with OSC.

[8] Morningstar (2024). Canadian Investors Stuck with ESG in 2023.

[9] Note that this is not a comprehensive review of ESG factors nor a compliance review of disclosures.

ESG Foundations

ESG Foundations

ESG refers to a collection of non-financial factors used to assess an organization or investment's practices and performance on various sustainability and ethical issues. Investors can consider ESG factors when investing, which can include identification of material risks, growth opportunities, and other normative goals.

Currently, there is no global standard definition of sustainable finance or ESG (including the issues that should fall under “E”, “S”, or “G”). The IFRS International Sustainability Standards Board’s (ISSB) publication on June 26, 2023:[10] IFRS S1 General Requirements for Disclosure of Sustainability-related Financial Information and IFRS S2 Climate-related Disclosures (together, the ISSB Standards), is important for the development of a global baseline for sustainability disclosure. However, IFRS S1 and S2 will not enter into effect in Canada until given effect, with or without modifications, by the Canadian Sustainability Board, and then action is taken by the Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA) to establish disclosure rules in Canada.

Despite the fact that a globally agreed taxonomy has not yet been achieved, ESG can be understood as:

- Environmental: Issues relating to the quality and functioning of the natural environment and natural systems. This includes, but are not limited to, climate change, biodiversity, air and water pollution and natural resource management.

- Social: Issues relating to the rights, well-being and interests of people and communities. This includes, but are not limited to, reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples, diversity and inclusion, data privacy and security, labour practices, supply chain management and human rights.

- Governance: Issues relating to the governance of underlying companies and other investee entities. This includes, but are not limited to, board structure and independence, business ethics, executive compensation, and shareholder rights.

[10] International Financial Reporting Standards (2023). IFRS S1 General Requirements for Disclosure of Sustainability-related Financial Information.

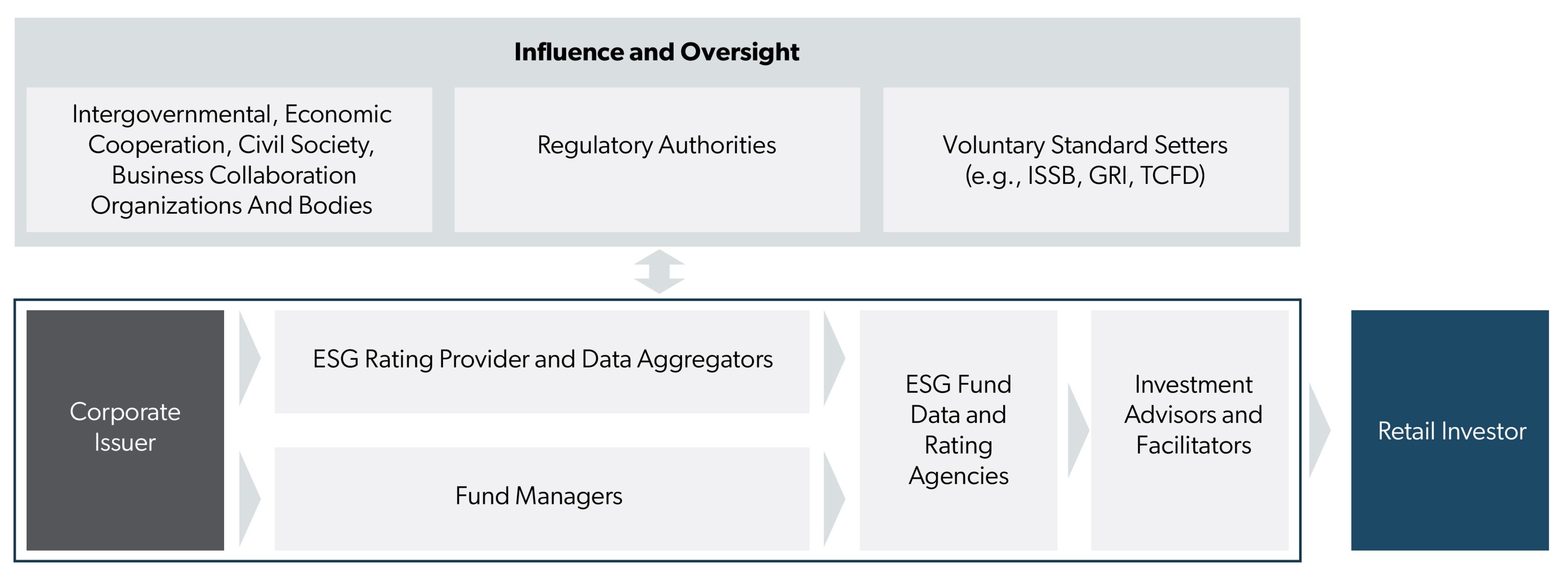

When retail investors make decisions to invest in ESG products, their selection of a fund may be influenced by the presence of ESG ratings or an ESG-related name. Within the ESG ecosystem, there are many different organizations involved. ESG investing has been facilitated by several key groups including institutions and intermediaries that support the manufacturing of fund products for retail investors, which include:

- Companies (corporate issuers) develop and share ESG related information

- Rating agencies evaluate this information and process data

- Fund managers leverage this data to identify holdings for ESG investment funds

- Fund rating agencies assess the investment fund’s ESG characteristics

See Figure 1 for a visual depiction of the value chain.

Figure 1: Retail ESG investing value chain.

Source: PwC Analysis

ESG information about corporate issuers is developed and dispersed differently from conventional financial information, and definitions and disclosure requirements are not yet standardized. There are gaps in data, regulation is still developing, and rating methodologies vary and may be opaque. This makes it challenging for retail investors to make investment decisions about such issuers based on ESG factors.

Investors who are interested in ESG investing may turn to funds with an ESG focus and rely on fund managers to evaluate the ESG information of individual companies.[11] However, this may expose investors in investment funds to greenwashing risk. Greenwashing is defined by the CSA in the context of investment funds as disclosure or marketing by the fund that intentionally or inadvertently misleads investors about the ESG-related aspects of the fund.[12]

Fund managers may also be subject to greenwashing themselves due to misleading corporate issuer disclosure, complexity in calculating emissions throughout a corporation’s value chain in the case of climate disclosure, as well as challenges associated with opacity and information inconsistency provided by ESG data and ratings providers. Note that greenwashing is not limited to environmental claims but can also include misleading claims about the socially responsible aspects of investment products.

[11] Retail investors that review corporate issuer ESG reporting and ESG ratings by rating agencies may be subject to greenwashing directly, however, the focus of this report is on investment funds and retail investors.

[12] Canadian Securities Administrators. (2022; revised 2024). CSA Staff Notice - 81-334 - ESG-Related Investment Fund Disclosure.

There are several organizations that collate, aggregate, and analyze data to provide quantitative measures to review ESG performance of companies. However, there is no standardized measurement of ESG factors. In addition, we speculate that the numerous different ratings provided by a myriad of organizations likely further confuses retail investors. See Table 1 for an example of the ratings by different companies.

Table 1: Key differences in ESG definitions and approaches by ratings agencies.

| Rating Agency | Sustainalytics | MSCI | Refinitiv | S&P Global |

| Coverage | 12,000 | 8,500* | >10,000 | >11,500** |

| Highest Score | 40+ | AAA | 100 | 100 |

| Lowest Score | 0 | CCC | 0 | 0 |

| Methodology | Key ESG issues split across E, S, and G: - Issues vary by industry - At least 70 indicators per industry Considered across: preparedness, disclosure, and performance | 37 key issues split across E, S, and G and 10 themes: - Climate change, natural resources, pollution & waste, environmental opportunities, human capital, product liability, stakeholder opposition, social opportunities, corporate governance, corporate behaviour | More than 500 ESG metrics across 10 main themes: emissions, environmental production innovation, resource use, workforce, human rights, community, product responsibility, management, stakeholders, CSR strategy | Weighted criteria score for each of the E, S, and G factors resulting from 1,000 data points from assessed values, text, checkboxes, documents |

| Data Sources | Publicly Available data: CO2 emissions; company reporting; 3rd party research; government databases; company disclosures | Macro data at segment or geographical level from academic, government and NGO databases | Annual reports, company websites, NGO websites, stock exchange filings, CSR reports, news Sources | Survey Questions: 100 question exploration, guided by 61 industry-specific approaches for each criteria score and publicly available data |

Source: Bien, Iqbal, Li, Stecher, & Manger (2021). Comparing Environmental, Social, and Governance Ratings Across Stock Exchanges. Global Economic Policy Lab.

In 2021, International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) noted some of the sources of the challenges related to the measurement of ESG. [13] They found that:

- There is little clarity and alignment on definitions, including on what ratings or data products intend to measure.

- There is a lack of transparency about the methodologies underpinning these ratings or data products.

- There is an uneven coverage of products offered, with certain industries or geographical areas benefiting from more coverage than others.

- There may be concerns about the management of conflicts of interest where the ESG ratings and data products provider or an entity closely associated with the provider performs consulting services for companies that are the subject of these ESG ratings or data products.

- There is a lack of communication with companies that are the subject of ESG ratings or data products.

[13] International Organization of Securities Commissions. (2021). CR02/2021 Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Ratings and Data Products Providers.

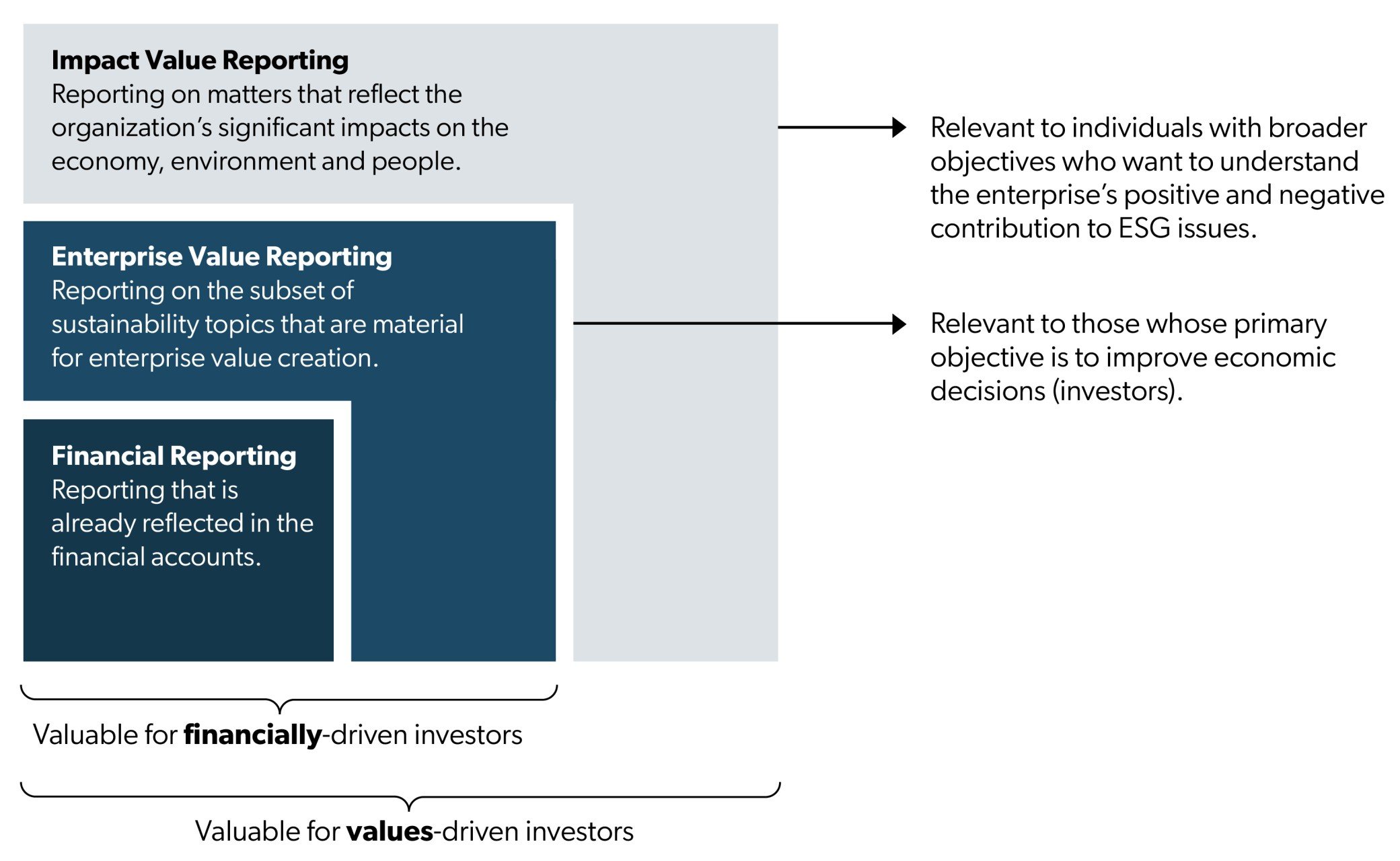

ESG ratings and the data produced by ESG ratings agencies can be one of several sources of information used by fund managers to develop ESG investment funds, which are then used in fund marketing. The ratings generally use an approach that assesses the sustainability-related financial risks and opportunities to the company (i.e., enterprise value), rather than measuring a company’s impact on the environment and/or society (i.e., impact value). This difference is evident when we consider voluntary ESG disclosure frameworks, where two distinct approaches exist for companies—enterprise and impact reporting (Figure 2).

Enterprise reporting focuses on financially material risks to the organization due to ESG factors. Impact reporting looks at the impact of the organization on ESG issues. For example, “water stress” is an issue often included in assessments of the “E” factor. In what might be counterintuitive and/or misleading for retail investors, water stress refers to whether communities have enough water for the factories to consistently operate, rather than the company's impact on the water supply of the communities where it operates.

Impact reporting is less established than enterprise reporting, and less aligned with conventional financial analysis (instead relying on hypothesis and non-traditional data sources). Therefore, impact reporting is less likely to be used for ESG ratings.

These different frameworks may be likely misunderstood by consumers of ESG data and ratings, as they may believe ESG data and ratings are based on impact-value when the data and ratings could reflect enterprise-value.

Figure 2: Illustration of the key reporting approaches and their interconnected nature

Source: CDP, CDSB, GRI, IIR, and SASB (2020), Statement of Intent to Work Together Towards Comprehensive Corporate Reporting

ESG products may be built using financial, enterprise-value, and impact-value reporting, ESG ratings, and proprietary research. There is a spectrum of approaches from enterprise-value focused on one end to impact-value focused on the other, with many possible variances. The five approaches commonly used to build ESG products are ESG integration, exclusionary screen, inclusionary screen, impact, and active (see Table 2).

Table 2: Spectrum of ESG investment themes

Objective | Integration Themes | Description |

Enterprise- value focused Image

Impact- value focused | ESG Integration | Incorporates ESG data, alongside traditional financial analysis, into the securities election process. |

| Exclusionary Screening | Exclusionary screens can often be categorized as either values-based or norms-based. Excludes, from the investment universe, companies, sectors, or countries involved in activities that do not align with the moral values of investors or with global standards. | |

| Inclusionary Screening | Tilts portfolio toward one of following:

| |

| Impact | Targets a measurable positive social and/or environmental impact. Investments are generally project specific and tend not to leverage ESG ratings. | |

Active (i.e., corporate engagement and stakeholder action) | Entails engaging with companies and voting company shares on a variety of ESG issues to initiate changes in behaviour or in company policies and practices. |

Some ESG investment themes use enterprise-value reporting while others use impact-value reporting, and others use a combination of both. As a result, retail investors may face difficulty understanding from the five ESG investment themes whether the approach to measurement is enterprise-value reporting, impact-value reporting, or both. Consequently, retail investors may purchase funds misaligned with their ESG investing intentions. Advisors could also face similar challenges. A combination of investment themes being used by fund managers when designing funds could exacerbate this challenge.

[14] This can often be treated as a separate strategy.

ESG Marketing

ESG Marketing

Prior to investing in ESG investment funds, retail investors may be exposed to ESG marketing developed by fund managers. Fund managers use several vehicles to market products and provide information to retail investors, including:

- Push marketing (direct-to-consumer advertising) and press releases

- Product names and product labels

- Websites and retail outreach channels: fund manager and product branding/ websites

- Fund documentation: prospectus, Fund Facts, fund factsheets, annual reports

Push marketing (direct advertising) and press releases refer to digital advertising of brands or products and press release statements regarding a fund manager or their products. Push marketing and press releases seem to serve two purposes:

- Engage with retail investors and promote a fund manager's brand as sustainably conscious and aware

- Update potential investors on new perspectives, approaches, or products that are aligned with ESG objectives

Product names and labels are a primary point of information for retail investors engaging with products, and often signal the intention of the fund.[15] Fund names may have the word “sustainable” or may align with a particular theme / objective such as “climate” or “women in leadership”. This is a message sent by fund managers and has been observed to influence investor behaviour.[16] The inherent complexity of ESG information makes it challenging to test and validate claims made by fund managers. Therefore, even with the best intentions, ESG marketing claims stand the risk of being misleading.

[15] Candelon, B. et al (2021). ESG-Washing in the Mutual Funds Industry? From Information Asymmetry to Regulation.

[16] El Ghoul, S., and A. Karoui. (2021). What’s in a (green) name? the consequences of greening fund names on fund flows, turnover, and performance.

Greenwashing can occur within the marketing of ESG investment funds. Greenwashing—defined by the CSA—occurs when a fund’s disclosure or marketing intentionally or inadvertently misleads investors about the ESG-related aspects of the fund.[17] Greenwashing poses a risk to investors and to the fostering of fair and efficient markets.

Continuous disclosure reviews by the CSA identified several areas of ESG-related fund disclosure for which there is a need for improvement to provide greater clarity to investors about ESG.[18] Observations from those reviews include:

- Some funds lacked detailed disclosures in their investment strategies about the specific ESG factors considered by the fund, including failing to identify or explain the ESG factors, or disclose how the factors are evaluated.

- Around two-thirds of the funds reviewed use negative screening as an investment strategy, but a small portion of those funds did not provide an explanation of the negative screening factors where they were not self-explanatory. A small number of the funds reviewed use multiple ESG strategies outside of negative screening but did not provide disclosure about how the various strategies work together, including the order in which they are applied during the investment selection process.

- Slightly over a third of the funds held investments in industries that, according to their exclusionary investment strategies, should not have been permitted. In addition, a fifth of the funds had portfolio holdings that appeared to be inconsistent with the fund’s name, investment objectives or investment strategies.

- Almost half of the funds disclosed ESG-specific risks in their prospectuses. More than half of the funds reviewed use proxy voting as part of their ESG strategies. However, more than half of those funds did not disclose their ESG-specific proxy voting policies and procedures in their prospectuses or Annual Information Forms (AIFs), as applicable.

- About three-quarters of the funds reviewed did not report on the changes in the composition of their investment portfolios due to the ESG-related aspects of their investment objectives and investment strategies. In addition, the majority of the funds reviewed did not report on their progress or status with regard to meeting their ESG-related investment objectives.

- Around one-third of the funds reviewed provided more detailed disclosure of their investment strategies in their sales communications than they did in their prospectuses. For several funds, there were discrepancies between their prospectuses and sales communications in the way that they described their investment strategies.

The CSA Staff Notice 81-334 also states that “the name and investment objectives of a fund should accurately reflect the extent to which the fund is focused on ESG, where applicable, including the particular aspect(s) of ESG that the fund is focused on.”[19] In June 2024, new provisions were added to Canada’s Competition Act that explicitly target greenwashing, which require businesses to have testing or substantiation to support certain environmental claims.[20]

[17] Canadian Securities Administrators (2022; revised 2024). CSA Staff Notice - 81-334 - ESG-Related Investment Fund Disclosure.

[18] Canadian Securities Administrators (2022; revised 2024). CSA Staff Notice - 81-334 - ESG-Related Investment Fund Disclosure.

[19] Canadian Securities Administrators (2022; revised 2024). CSA Staff Notice - 81-334 - ESG-Related Investment Fund Disclosure.

[20] Competition Bureau Canada (2024). Public consultation on Competition Act’s new greenwashing provisions.

There are five main types of marketing themes used by fund managers which may have associated misleading claims, whether intentionally or not, therefore leading to greenwashing (see Table 3).

Table 3: Taxonomy of ESG marketing themes and greenwashing risk

| Marketing Theme | Description | Greenwashing Risk |

| Best-in-class | Funds are marketed as having exposure to companies with the highest ESG ratings relative to their peers. | Assessed relative to other organizations within the same industry and so a high performing oil and gas producer may be included, where an average scoring new energy vehicle company is excluded. Also, these funds could be reporting enterprise risk value while the investor is expecting to measure impact value. |

| Fund ESG Rating | Funds are marketed according to their 3rd party ESG rating, which is assigned with respect to comparable funds. | Issues with measurement (i.e., standardization and transparency of what is being measured), comparing different industries, and some fund rankings may include funds that are not for sale in the applicable jurisdiction. |

| Inconsistent Focus | Funds where the name doesn’t entirely align with the objectives. For example, an “ESG” fund that only addresses environmental issues, without disclosure that only environmental sustainability is considered by the fund. | The inconsistent focus marketing theme refers to misalignment between the product or brand marketing and the product investment strategies. This may include an absolute misalignment, in that a product has no ESG focus but is marketed as such, or relative misalignment within ESG in that it is marketed towards one factor but invests according to another. |

| Positive Outcome | Funds are marketed with a focus on the impact that it could have on ESG objectives. “Be part of the change” is an example of this type of messaging. | The emotive language often found in this marketing theme, is often not reinforced by appropriate measurement of the fund’s impact. Greenwashing is most likely to be found in this marketing theme because tangible measurement is often difficult. This can be attributed to inconsistent ESG impact disclosure by corporate issuers combined with the difficulty in measuring impact against global sustainability objectives, or a lack of any positive impact achieved. |

| Success Metrics | Licenses aggregated holding ESG data to create a comparative value against the financial performance benchmark. | The metrics used and the underlying issues with that data/measurement could lead to misleading information. |

ESG and Retail Investors

ESG and Retail Investors

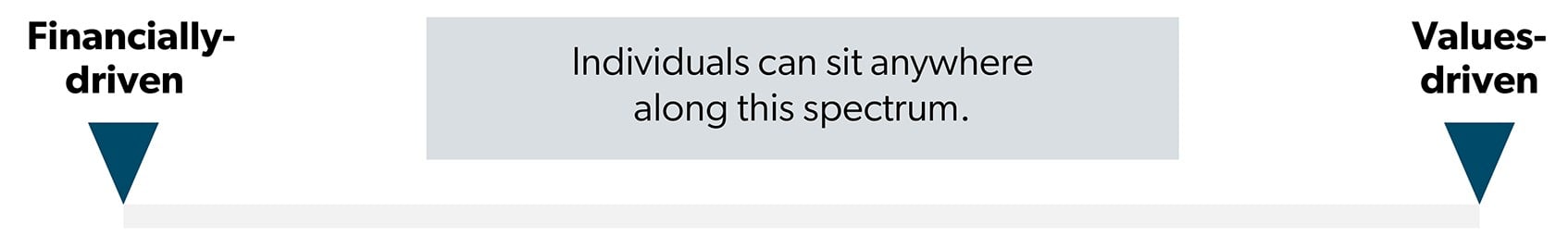

Investors’ beliefs and attitudes towards ESG can significantly influence their investment decisions. These beliefs may motivate investors to invest in ESG investment funds. ESG investors can be classified into two types—those who are financially-driven versus values-driven (Figure 3). An investor can be anywhere along the spectrum.

- Financially-driven investors participate in sustainable investing to protect their investment portfolio from potential risks and to identify opportunities for enhanced returns.

- Values-driven investors are motivated by social, political, economic, and/or environmental reform—and they are driven by the desire and willingness to affect change in the world.

Figure 3: Types of ESG investors

Source: PwC Analysis

Given their differing values, these types of investors engage in different investing decisions. Retail investors with strong intrinsic motivations aligning with ESG issues may be more willing to accept a reduced rate of return (due to a combination of higher fees and poorer fund performance).[21] This is evident in our experiment as well (discussed later in this report), where we observe that values-driven investors are more willing to accept higher MERs for funds with higher ESG ratings compared to their financially-driven counterparts.

[21] Riedl, A., & Smeets, P. (2017). Why do investors hold socially responsible mutual funds? The Journal of Finance, 72(6), 2505-2550.

When retail investors become aware of ESG investing, they may consider ESG investment funds. When investors begin their research on ESG investment products, they likely examine three forms of information: product naming, ESG ratings, and marketing materials. Product names can play a key role when examining ESG investments, as many retail investors may not spend significant effort in exploring and deliberating beyond product names.[22] As such, fund naming may drive investment decisions as a cue for product contents.

ESG ratings are also used to examine ESG investment funds. Ratings provide investors with a simpler measurement of the product. In addition, fund manager marketing material is another key form of information for retail investors. These resources provide a substantial source of ESG information and can help to update retail investor beliefs and perceptions of ESG investing and products. Simultaneously, these marketing materials may expose retail investors to somewhat confusing and potentially misleading marketing, and subjects them to information asymmetry (as fund managers may be privy to some additional information).

[22] Ontario Securities Commission (2020). Investor Experience Research Study.

Throughout their ESG investing experience, retail investors may encounter various behavioural barriers. Initially, they may be prone to the bandwagon effect,[23] where simply seeing others invest in ESG encourages them to do the same. As their interest in ESG investing grows, they will likely start examining different ESG investment funds. However, they may face information overload[24] due to the numerous ESG investment funds available, potentially leading to decision paralysis.

Even after narrowing down their options, some investors might experience effort aversion.[25] When motivation is low, they tend to choose the path of least resistance, avoiding the deliberation required to comprehend complex ESG data. Instead, they might rely solely on ESG ratings to compare funds. This can also make them susceptible to the halo effect—where positive impressions about a fund’s rating extend to other attributes (i.e., good ratings are associated with good returns).[26]

Another behavioural barrier tied to the emotional aspect of investing in ESG investment funds is the affect heuristic[27]. This can cause investors to make decisions based on positive emotions towards a fund rather than on rational metrics, simply because it “feels good” to invest in ESG investment funds. We speculate that this tendency is more pronounced among values-driven investors compared to those focused on financial returns.

[23] Leibenstein, H. (1950). Bandwagon, snob, and Veblen effects in the theory of consumers' demand. The quarterly journal of economics, 64(2), 183-207.

[24] Malhotra, N. K. (1984). Information and sensory overload. Information and sensory overload in psychology and marketing. Psychology & Marketing, 1(3 - 4), 9-21.

[25] Dreisbach, G., & Jurczyk, V. (2022). The role of objective and subjective effort costs in voluntary task choice. Psychological Research, 86(5), 1366-1381.

[26] Leuthesser, L. et al. (1995). Brand equity: the halo effect measure. European journal of marketing.

[27] Slovic, P. et al. (2007). The affect heuristic. European journal of operational research, 177(3), 1333-1352.

The minimization of these biases and heuristics can lead to better investing decisions. To better navigate investing in ESG investment funds, retail investors should:

- Determine the importance of financial and non-financial returns, the trade-offs they are willing to make, and clearly understand their motivations to invest.

- Recognize that information in this space is voluminous and can be of poor quality. Triangulate information and avoid relying on singular sources where possible.

- Recognize it is difficult to measure the impact of products and companies on ESG issues.

- Realize that marketing may look to capitalize on the desire to create an impact with their investments.

- Understand ESG information before using it to inform decisions. This is particularly relevant for ESG ratings, where ESG ratings differ and often represents risk rather than impact, and different rating scales of ESG could drive investment decisions.

- Be aware that advisors may be facing similar challenges to retail investors in dealing with inconsistent information and processing that information.

A combination of access to robust data and information standardization, along with a better understanding of the common heuristics and biases in investing, may improve ESG investing decisions. Financial advisors can often guide investors, who provide recommendations in accordance with their Know-Your-Product and Know-Your-Client obligations, which may include ESG considerations.[28] In addition, rating agencies and fund managers have a significant role to play in providing more clarity and transparency with respect to the methodologies and objectives of the funds, and being careful to avoid marketing that may be confusing or misleading.

[28] Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada (2021). Know-your-client and suitability determination for retail clients. & IIROC. (2021). Product Due Diligence and Know-Your-Product.

Financial advisors can play an important role in assisting retail investors, especially when investors consider their options regarding ESG investment funds. In fact, when advisors are involved, they can significantly impact the ESG investing experience by absorbing some of the effort associated with processing ESG information. Their financial literacy, and product knowledge (as reflected in the Know-Your-Product requirements) position them to support retail investors. However, advisors may face many of the same challenges associated with the complex public ESG information as individual retail investors (although they may face fewer financial barriers in accessing some information, such as ESG ratings). In some cases, the complexity and unfamiliarity of the ESG landscape may deter advisors from recommending ESG products.[29] It is therefore recommended that advisors’ proficiency on ESG knowledge (i.e., information and/or ESG investment strategies) be supported and strengthened.[30]

[29] Responsible Investment Association. (2021), 2021 RIA Investor Opinion Survey.

[30] The Client Focused Reforms changes to Know-Your-Product (KYP) requirements require registered firms to assess and individuals to understand the relevant aspects of the securities that they are considering making available to clients. Firms are expected to have the appropriate skills and experience to perform the necessary assessment of all securities to be made available to clients. Additional training and/or proficiency requirements are necessary for their registered individuals to understand ESG securities and make appropriate suitability determinations. Please refer to National Instrument 31-103 and Companion Policy 31-103CP for additional details.

National Instrument 31-103 Registration Requirements, Exemptions and Ongoing Registrant Obligations and Companion Policy to NI 31-103 CP Registration Requirements, Exemptions and Ongoing Registrant Obligations

Experiment

Experiment

We conducted a scientifically rigorous experiment to help facilitate data-driven, evidence-based regulation. The objective of the experiment was to measure retail investors' intentions, values, and attitudes toward ESG to identify how they translate into retail investors’ decision-making. We examined the effects of specific fund attributes (including ESG related attributes) that are found in manufacturers’ key fact sheets, on investor behaviour. In addition, we examined the susceptibility of Canadian retail investors to the effects of “greenwashing.”

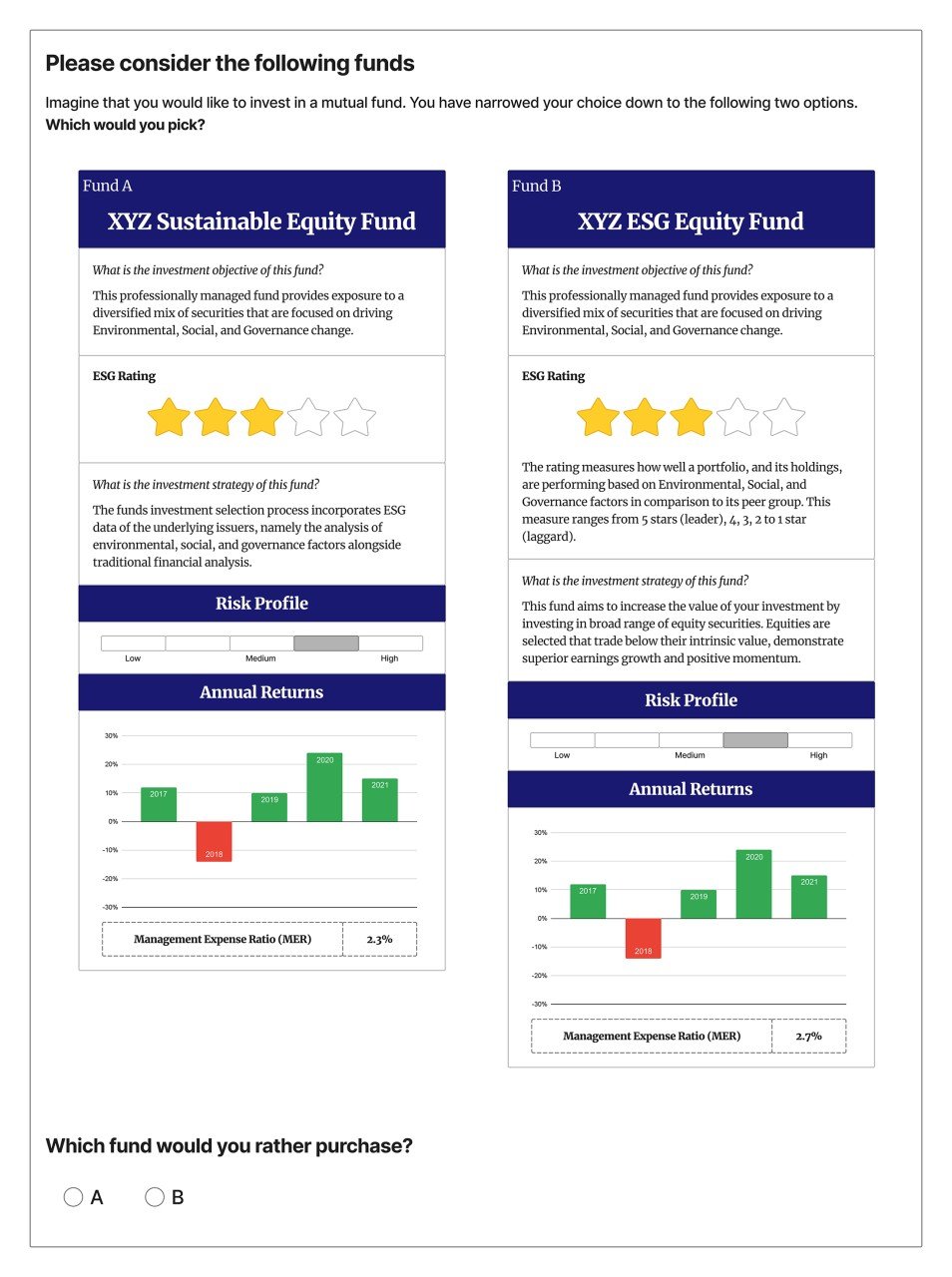

To examine retail investors’ attitudes, values, and intentions regarding ESG investment funds, we employed an experimental paradigm known as a discrete choice experiment (DCE). A DCE is a quantitative research method that is used to understand individual preferences by presenting them with sets of hypothetical choices. In our experiment, we asked participants to choose between two investment funds—with each choice having a total of 8 attributes displayed within a key fact sheet (See Table 4 for description of attributes).

Both choices include the same attributes, however, their levels (i.e., versions of the attributes) may differ, as they are randomly selected from a predetermined list. For example, while both choices will have a fund name, the names may be different, such as ESG Equity Fund or Sustainable Equity Fund. In our experiment, each attribute contains at least 2 levels. See Appendix A for details about levels.

We then randomly generated two new investment fund choices for participants and asked them to choose one of the two new investment funds. We did this 12 times in total for each participant. By examining participants’ choices, we can determine which attributes within an ESG investment fund drive the selection of ESG investment funds.

Table 4: The attributes included in our key fact sheet.

Attribute | Description |

| Fund Names | Draw attention to and/or build associations about the purported activities, strategies, or impacts of the fund. |

| Investment Strategies | Articulate to participants how the fund will be invested to meet its stated objectives. |

| ESG Ratings | Reflect assessments of a fund's exposure to ESG-related risk vis-a-vis the portfolio's holdings. Ratings were either represented visually (out of 5 stars), or with letters grades. We also presented some funds with no ratings as a comparison. |

| Rating Explanations | Include information about the meaning of the ESG rating. |

| Investment Objectives | Clarify the goals of the fund. |

| Risk Profiles | Indicate the volatility of the fund and is based on how much the fund’s returns have changed from year to year considering its holdings. |

| Past Performance | Provide historical data on fund returns. |

| Management Expense Ratios (MERs) | The total of the fund’s management fee (which includes any trailing commission) and its operating expenses. |

Each key fact sheet contained these 8 attributes (sometimes excluding the rating explanations). See Appendix B for an example of the two choices of the key fact sheets.

Choice sets may include a clear explanation of ESG ratings. Unlike other elements of our choice sets, this is not commonplace in the market. It can be considered an intervention, inspired by the observation made earlier in this report, that a lack of understanding around ESG ratings may adversely affect retail investor decision-making.

A total of 961 retail investors’ data were analyzed in the experiment.[31] Recall that each participant was given a series of 12 choices between two fund fact sheets and asked to select which of the two funds they preferred. In total, participants made 11,532 choices—each time selecting between two funds. Following the DCE, participants answered questions to assess their attitudes toward investing and financial product ownership. Finally, they filled out a demographic questionnaire.

A choice-based conjoint analysis—an analysis commonly used for DCEs—was used to analyze the results. This approach analyzes how much influence a particular level (e.g., a medium-to-low risk profile) has on the probability of an option being chosen. It also provides a comparable and quantitative metric that allows for the comparison of all levels within an experiment. A machine learning algorithm called K-modes clustering was then used to group investors that shared similar attitudes and values. This allowed us to explore whether differences in attitudes toward the relationship between sustainability and financial markets would result in measurable differences in behaviour.

[31] Participants were self-registered in a paid participant pool and self-selected into our experiment. Although selection is non-random, these participants provide valuable insights in a DCE, as the experiment’s design isolates the effect of fund attributes on decision-making, and we are able to observe different preferences for different subgroups.

Attribute and Level Importance

Level Importance

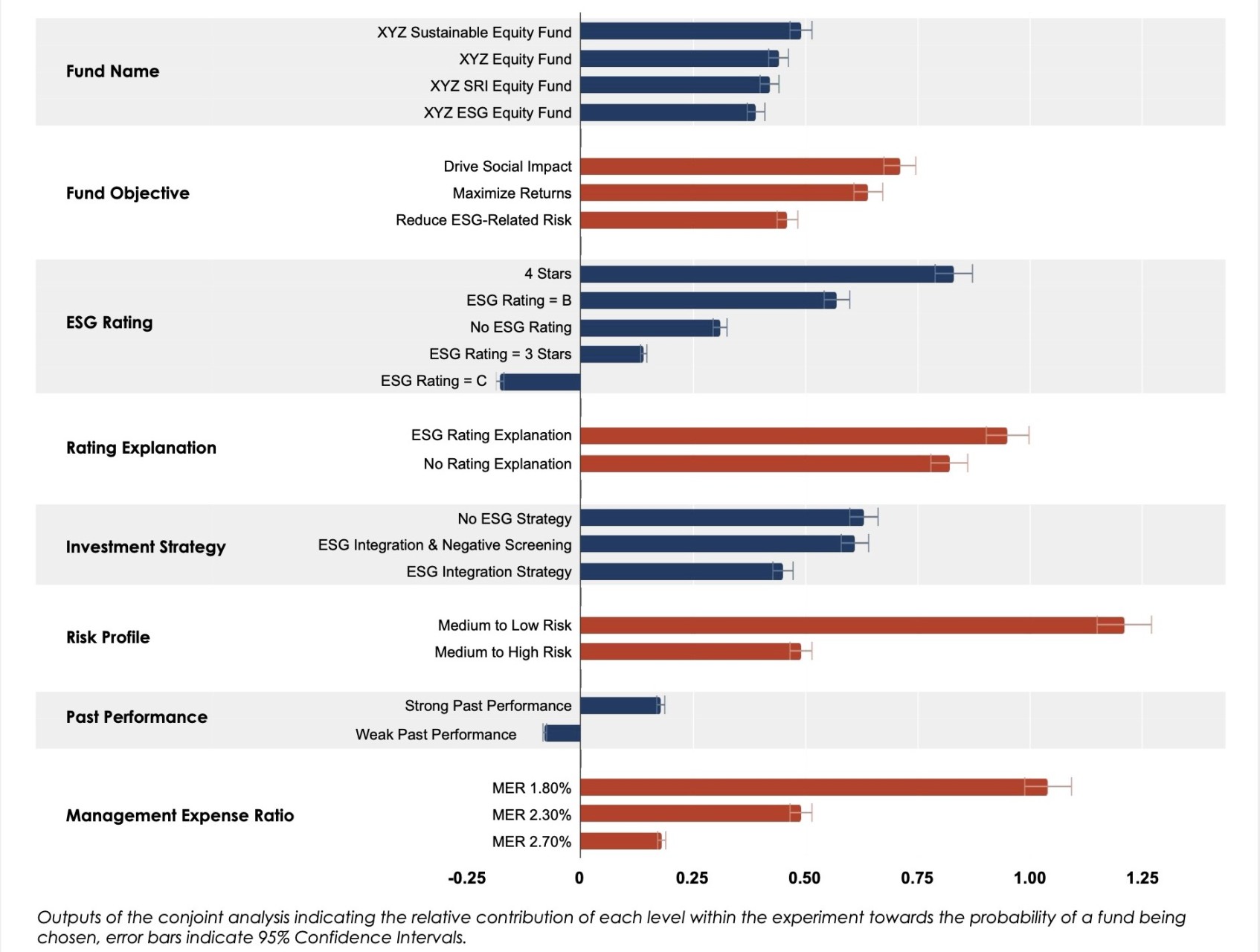

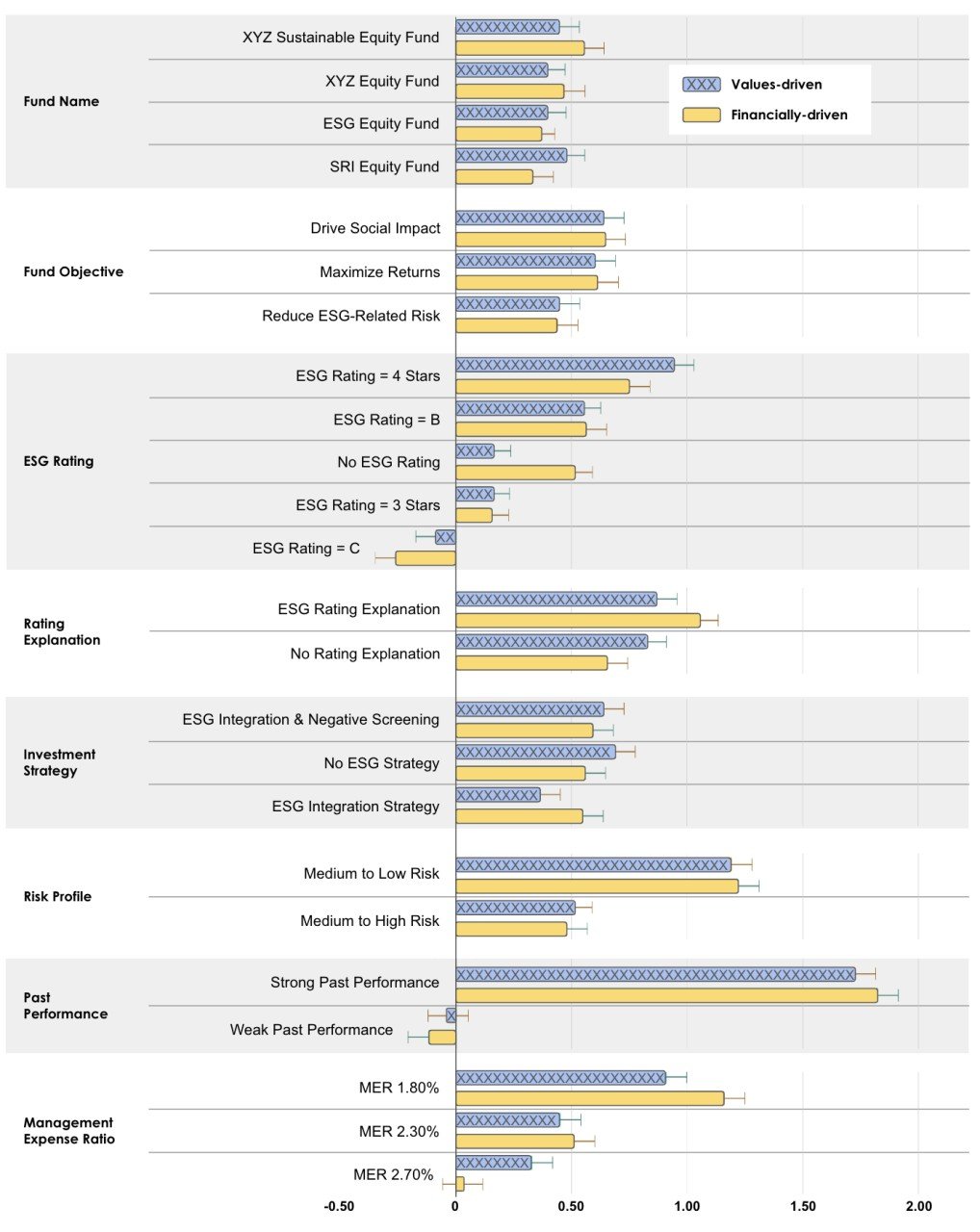

The levels (i.e., versions) included in our DCE are presented in Figure 4, ordered by absolute level of influence in fund selection, and categorized by attribute. Each bar represents the relative contribution of each level toward choice. The greater the value, the greater the influence. Positive values indicate that inclusion of a level within a fund increases the probability of that fund being chosen, while a negative value indicates that its inclusion makes a fund less likely to be chosen. It is important to note that a conjoint analysis is not a zero-sum calculation, as every element could be positively predictive of choice, however, to varying degrees.

Figure 4. Influence of Levels by Attribute

Outputs of the conjoint analysis indicating the relative contribution of each level within the experiment towards the probability of a fund being chosen, error bars indicate 95% Confidence Intervals.

Fund Name

There were no statistically significant differences in the selection of the four fund names contained within the experiment. While there was not a statistically significant effect of fund names in the experiment, it is possible that in another context such as an advertisement or marketing materials, fund names may influence retail investors.

Fund Investment Objectives

Fund investment objectives focused on either a) maximizing financial returns or b) driving positive social impact outperform the objective of reducing ESG-related risk. Two types of investment strategies were selected significantly more often than ESG integration alone:

- A strategy that included prioritizing stocks that trade below intrinsic value (No ESG Strategy).

- A strategy that coupled ESG integration with the inclusion and exclusion of certain companies (Integration and Screening). The Integration and Screening strategy is commonly used among ESG assets that are available for purchase.

Ratings

Our experiment analyzed ESG ratings along two dimensions: the strength of the rating, and the format in which ratings were communicated. The rating system used in the experiment is similar, but not identical, to what is prevalent in the market (an image representation and letters were used but not in the same manner). The strength of a given rating was used to determine the difference between one rating’s contribution toward choice relative to the other rating’s contribution toward choice.

Within rating formats, retail investors favoured funds that contain stronger ESG ratings, with:

- A 4-star rating performing 7% better than a 3 star.

- A B rating performing 8% better than a C rating.

Across formats, retail investors favoured funds with star-based ratings over letter grades, with:

- A 4-star rating (2nd best of 5-star range) performing 3% better than a B rating (2nd best letter grade).

- A 3-star rating (3rd best of 5-star range) performing 3% better than a C rating (3rd best letter grade).

Interestingly, we also see that the absence of an ESG rating was preferred to an ESG rating of either 3 stars or C, suggesting that there is a threshold at which ESG ratings transition from a motivating factor to a deterrent.

Rating Explanation

Given our interest in whether retail investor decision-making is impacted by a misunderstanding of ESG’s intended function, a plain-language explanation was included as a possible feature on the key fact sheets. To our knowledge, this is the only feature in our experiment that does not reflect common practice in the market.

We might expect that confusion around ESG ratings could result in values-driven investors opting to purchase ESG products, under the incorrect assumption that they are associated with positive ESG impact. If this were indeed the case, the inclusion of a clear explanation would reduce the frequency of a fund’s selection. Contrary to our hypothesis, it was found that the inclusion of an explanation was positively predictive of choice, as choice sets containing a clear explanation was selected significantly more often than choice sets lacking an explanation. A possible interpretation of this finding is that participants simply found having additional information about the fund (regardless of what kind of information) to be more compelling.

Risk Profile, Past Performance, and MER

Three attributes that did not have direct ties to ESG were also included: risk profile, past performance, and MER. All three attributes contained levels that were strongly predictive of a particular fund being chosen. Past performance was especially significant, containing the single strongest-performing level across all attributes.

Retail investors preferred lower risk, stronger past performance, and low MERs, all of which are indicative of efficient investment and administration of a fund. This indicates the reliability of the results: while preference for various ESG or non-ESG elements is subjective, in the context of these three elements, participant behaviour was in alignment with what would be expected from investors trying to optimize fund performance. However, retail investors may have incorrectly assumed that past performance is a good predictor of future returns.

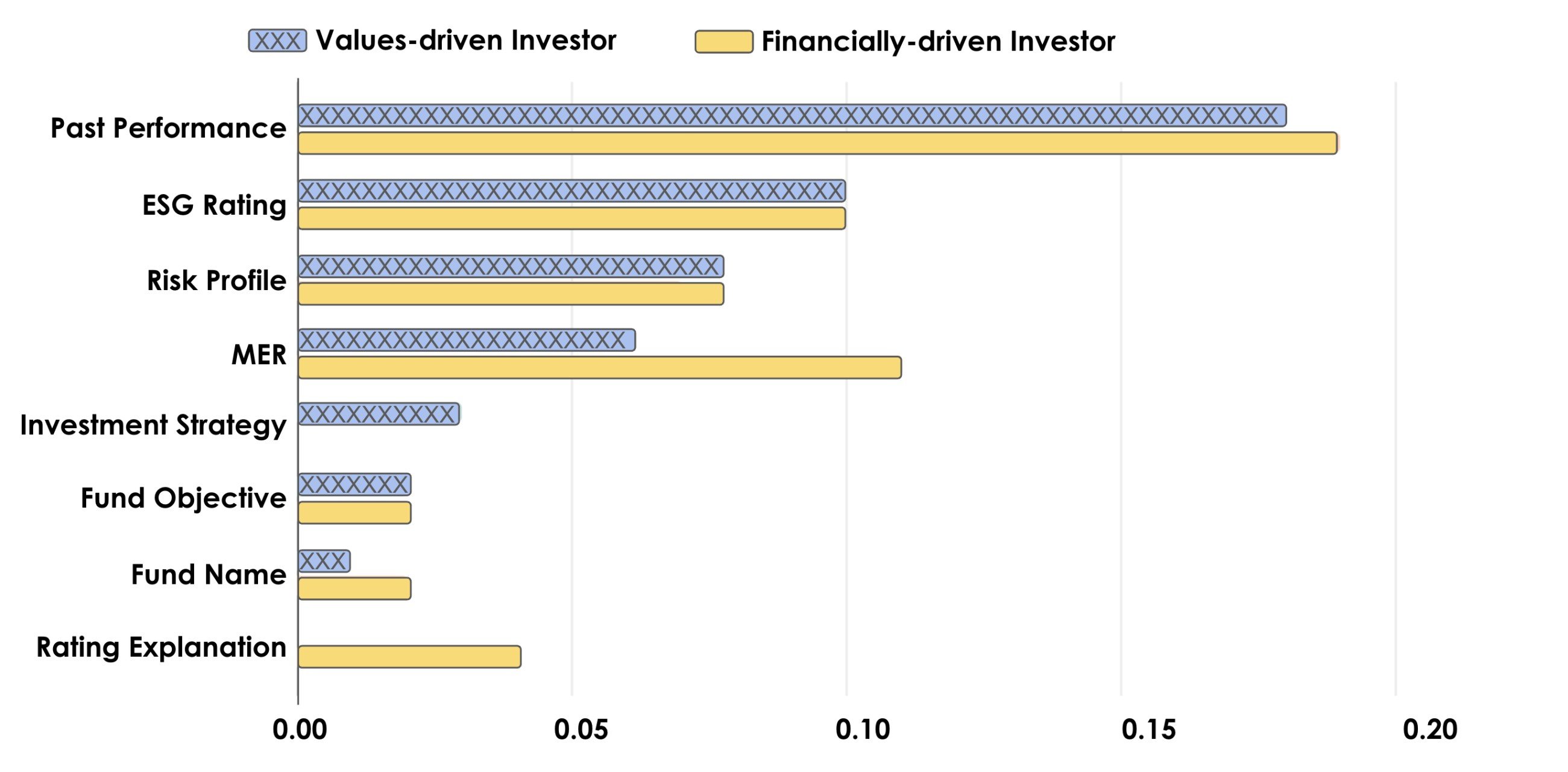

Attribute Importance

The relative importance of attributes by examining the difference in utility between the best- and worst-performing levels was calculated (see Figure 5). In the experiment, past performance had the highest degree of within-attribute variability: funds with strong past performance were much more likely to be chosen, while funds with poor past performance were much less likely to be chosen. Past performance was the most important attribute in the context of the experiment.

Of note, ESG rating stands apart as the second most important attribute, driven by the meaningful disparity between star and letter ratings. In other words, retail investors’ preference for star-based ratings over letter ratings was so strong that this attribute ended up being more influential than any of the more “traditional” fund attributes assessed, except for past performance. At the other end of the spectrum, fund name and investment strategy are relatively unimportant for Canadian retail investors.

Figure 5. Fund Attribute Importance

Attitudinal data illustrating the relative importnace retail investors place on fact sheet attributes in investment decisions.

Profiling Canadian Retail Investors

Retail investors’ responses to nine questions about investing attitudes and values were used for segmentation. There were two distinct segments within the sample:

- Values-driven investors (492 respondents; 51%) were characterized by a stated willingness to trade returns for sustainable outcomes.

- Financially-driven investors (469 respondents; 49%) were characterized by a focus on more traditional outcomes such as return-on-investment (ROI).

The two segments were compared in terms of fund selection within the DCE (see Figure 6). Both segments were similar in their demographics and in their assessment of fund name, past performance, fund objective, and risk profile. However, there were several key differences. Of note, values-driven investors were less responsive to ESG integration strategies than their financially-driven counterparts. Financially-driven investors, in practice, displayed indistinguishable responses to all three of the strategies outlined as part of our DCE, while values-driven investors were less influenced by ESG integration strategies. Also, values-driven investors were more responsive to an ESG rating of 4 stars, relative to their more enterprise-minded peers. Similarly, values-driven investors were comparatively less likely to select a fund that lacks an ESG rating altogether.

The choices of values-driven investors did not appear to significantly differ depending on whether key fact sheets contained a rating explanation. Financially-driven investors, however, were more likely to select a fund with an ESG rating if that rating was coupled with a clear explanation. One potential explanation for this finding is that financially-driven investors found the ESG rating and/or the fund more valuable after understanding the meaning of the ESG rating.

When we look at MER, we can see willingness to engage in a trade-off between returns and ESG impact. Values-driven investors were comparatively less likely to select a fund with a low MER, and more likely to select a fund with a high MER. This suggests that values-driven retail investors may be willing to make some financial sacrifice in exchange for a more sustainable portfolio or they may hold an erroneous belief that ESG investment funds require higher MERs.

Figure 6. Influence of Levels by Segment

Attitudinal data indicating the relative importance of each individual fact sheet attribute to retail investors as segmented by retail investor type.

Differences between the profiles are perhaps better understood when framed around attribute importance (see Figure 7). MER, as an attribute, was considerably more important for financially-driven investors, consistent with their preference for low MERs and aversion to high MERs relative to values-driven investors. Values-driven investors were comparatively more influenced by investment strategy. However, as discussed above, this was not driven by any impact-oriented fund strategies, but instead a relative aversion to ESG integration strategies.

Figure 7. Attribute Importance by Segment

Attitudinal data indicating the relative importance of each individual fact sheet attribute to retail investors as segmented by retail investor type.

Susceptibility to Greenwashing

In the DCE, there are several iterations of key fact sheets that could be construed as greenwashing, as there can be iterations that have mismatches between attributes, such as mismatches between fund names (e.g., “ESG” Fund) and investment strategies (e.g., no ESG strategy). Another example is a mismatch between Fund names (e.g., “ESG” Fund) and Fund Objectives (e.g., Maximized Returns). The randomization of the DCE approach allows for some key fact sheets to contain greenwashing, which permits us to observe the greenwashing effect on retail investors. Based on the analysis of retail investors’ choices, retail investors were not sensitive to these mismatches in the attributes, as these mismatches did not influence their selection of the funds (even though they should be selecting these “greenwashed” funds less frequently). This suggests that Canadian retail investors may face risk from greenwashing of products available in the market.

In addition, when there is no ESG rating, funds that contain the term “sustainable” were 14% less likely to be chosen by participants compared to the other fund option. However, this effect was not found for fund names that contain “ESG” and “SRI” (socially responsible investing). The lack of any discounting (i.e., reduction in the frequency of fund selection) for “ESG” or “SRI” could be interpreted as participants’ susceptibility to greenwashing, as participants may believe that having “ESG” or “SRI” terms in the fund names mean that the fund contains ESG-related assets.

Key Findings

- The ESG rating stood out as one of the most important attributes influencing consumer choice—second only to a fund’s past performance.

- The strength and format of the rating (letter grade and number of stars) were both impactful attributes.

- Higher ESG ratings had more positive influence on fund selection than lower ESG ratings.

- Star-rated funds had more positive influence on fund selection than letter-rated funds.

- The absence of an ESG rating was preferred to an ESG rating of either 3 stars or C, suggesting that there is a threshold at which ESG ratings transition from a motivating factor to a deterrent.

- Cluster analysis revealed two distinct segments of Canadian retail investors:

- Both segments were similar in their demographics and in their assessment of fund name, past performance, fund objective, and risk profile. They differed in their valuations of fund investment strategies, ESG ratings, rating explanations, and MER.

Values-Driven Investors | Financially-Driven Investors |

|

|

- Retail investors were not sensitive to mismatches in the attributes, such as a mismatch between a fund name (e.g., “ESG”) and its investment strategy (e.g., No ESG Strategy), as these mismatches did not influence their selection of the funds. This suggests that retail investors may face risk from greenwashing of products available in the market.

Conclusion

Conclusion

In this report, we examined how retail investors navigate the complicated and confusing ESG landscape. We discussed the key groups and their relationships within ESG retail investing, which include regulators, institutions, intermediaries, and retail investors. We noted that ESG information is not standardized, and that there are gaps in data, and information production methodologies are inconsistent and often opaque.

We discussed the role of fund managers within ESG retail investing, and the common strategies fund managers use to manufacture and market ESG products. Given the complexity of the ESG information landscape, some retail investors—especially less sophisticated investors—may rely on fund manager marketing to fill information gaps. This dependency and information asymmetry can leave retail investors vulnerable to confusion and/or misleading information. In addition, retail investors’ confidence in ESG may be negatively impacted by “greenwashing”, which can include exaggerated claims of ESG performance by companies and fund managers or exaggerated claims about the ESG focus or strategies of a fund.

As retail investors seek to invest in ESG investment funds, they must navigate complex information, while accounting for their own beliefs, attitudes, and motivations. Retail investors investing in ESG are likely to encounter a number of behavioural barriers and biases. Retail investors and their advisors should be aware of heuristics and biases to make better informed decisions. We have discussed several strategies to overcome these heuristics and biases.

During the retail investors’ behavioural experience, they may choose to invest, and thus, we examined and identified the key influences on fund selection through a scientific experiment. Within our experiment, there were several key findings of note. With regards to the varying formats in which ESG ratings are presented to retail investors, our experiment showed that retail investors are more positively influenced by graphical representations of ESG ratings (in this case, stars) compared to letter-grade rating (in this case, A to F). This suggests that retail investor decision-making may not only be swayed by the quality of the funds that they consider, but by the arbitrary way that information is presented. Establishing clear standards for the construction and communication of ESG ratings may thus be a crucial step in protecting investors and ensuring a fair competitive landscape.

Our experiment’s results also showed that investors may be susceptible to greenwashing. Retail investors were not sensitive to mismatches in the attributes, such as a mismatch between a fund name (e.g., “ESG”) and its investment strategy (e.g., No ESG Strategy), as these mismatches did not influence their selection of the funds. This suggests that retail investors may face risk from greenwashing of the products available in the market.

We also were able to identify different types of ESG investors. Of note, values-driven investors tend to conflate ESG with positive impact more than financially-driven investors. Retail investors that are values-driven are more likely to be influenced by ESG ratings in comparison to investors who are more focused on returns. In particular, values-driven retail investors may be willing to make some financial sacrifice (in the form of MERs) in exchange for a more sustainable portfolio or hold an erroneous belief that ESG investment funds require higher MERs.

Implications

The lack of standardization in ESG definitions and ratings is a critical issue that can lead to inadvertent and deliberate greenwashing. Even without deliberate greenwashing, ESG ratings can mislead retail investors, who believe they are investing in impactful companies aligned with their ESG values, when in fact they are often investing in ESG risks. It is unlikely that retail investors fully understand ESG ratings, yet these ratings are a particularly important factor when selecting ESG investment funds. The different types of ratings and lack of clarity around ratings allow manufacturers of these funds to potentially exploit investors’ tendency to rely on ESG ratings. Values-driven investors are particularly affected, as they are more willing to sacrifice returns, including higher MERs and potentially lower performance, to support funds they believe are making a positive impact. Based on these findings the OSC’s Research and Behavioural Insights Team recommends that stakeholders including authorities should incorporate the following to combat these challenges:

- Strive towards Clarity in ESG Definitions and Ratings

- Clarity around or potential standardization of ESG ratings to eliminate confusion and prevent greenwashing. This will support that ESG ratings that are consistent and comparable across different funds and products.

- Educate Investors

- Improve retail investors’ understanding of ESG investing through education and outreach, including the differences between ESG risks and impacts, as well as being able to identify signs of greenwashing. This will empower investors to make decisions that truly align with their values.

- Strengthen Advisor Proficiency

- Promote financial advisors training on ESG investing to better support their clients.

In sum, these findings are crucial as they help the OSC and stakeholders understand the influence of ESG factors on retail investment decision-making and behaviour, including susceptibility to greenwashing. Recognizing the diversity in retail investors’ preferences and behaviours is a key element in supporting informed decision-making. As an empirically driven regulator, we will continue to further our understanding of retail investor behaviour and decision-making with respect to ESG factors, and to share our findings.

Authors & Appendices

Authors

Ontario Securities Commission:

Matthew Kan

Senior Advisor, Behavioural Insights

[email protected]

Marian Passmore

Senior Legal Counsel, Investor Office

[email protected]

Meera Paleja

Program Head, Research and Behavioural Insights

[email protected]

Kevin Fine

Senior Vice President, Thought Leadership

[email protected]

Acknowledgements to:

PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC)

The Decision Lab

Attributes and Levels

Attribute | Label | Level |

|---|---|---|

Fund Name | XYZ Sustainable Equity Fund | XYZ Sustainable Equity Fund |

XYZ ESG Equity Fund | XYZ ESG Equity Fund | |

XYZ SRI Equity Fund | XYZ SRI Equity Fund | |

XYZ Equity Fund | XYZ Equity Fund | |

Investment Strategy | ESG Integration | This fund’s investment selection process incorporates ESG data of the underlying issuers, namely the analysis of environmental, social, and governance factors alongside traditional financial analysis. |

No ESG strategy | This fund aims to increase the value of your investment by investing in a broad range of equity securities. Equities are selected securities/shares/stocks that trade below their intrinsic value, demonstrate superior earnings growth, and show positive price momentum. | |

Integration & Screening | This fund uses general ESG integration, positive screening, and exclusionary screening by industry. Any industries involved in activities that do not align with the environmental, social, and/or governance values are excluded from the fund holdings. | |

ESG Rating | No Rating | No Rating |

B | B | |

C | C | |

3-Star | 3-Star | |

4-Star | 4-Star | |

Rating Explanation | With Explanation | This rating measures how well a portfolio and its holdings are performing based on environmental, social, and governance factors in comparison to its peer group. This measure ranges from A (leader), B, C, D to F (laggard). |

With Explanation | This rating measures how well a portfolio and its holdings are performing based on environmental, social, and governance factors in comparison to its peer group. This measure ranges from 5 stars (leader), 4, 3, 2 to 1 star (laggard). | |

No Explanation | No explanation | |

Fund Objective | Enterprise Value | This professionally managed fund provides exposure to a diversified mix of securities with environmental, social, and governance characteristics. |

Impact | This professionally managed fund provides exposure to a diversified mix of securities that are focused on driving positive environmental, social, and governance change. | |

Maximized Returns | This professionally managed fund provides exposure to a diversified mix of securities designed to deliver year-over-year growth. | |

Risk Profile | Medium to Low | Medium to Low |

Medium to High | Medium to High | |

Past Performance | Better Returns | Image

|

Worse Returns | Image

| |

Management Expense Ratio (MER) | MER 1.8% | 1.80% |

MER 2.7% | 2.70% | |

MER 2.3% | 2.30% |

An example of the two choices of key fact sheets.

Bien, Iqbal, Li, Stecher, & Manger (2021). Comparing Environmental, Social, and Governance Ratings Across Stock Exchanges. Global Economic Policy Lab.

Canadian Securities Administrators (2020). 2020 Investor Index.

Canadian Securities Administrators. (2022; revised 2024). CSA Staff Notice - 81-334 - ESG-Related Investment Fund Disclosure.

Candelon, B. et al (2021). ESG-Washing in the Mutual Funds Industry? From Information Asymmetry to Regulation.

Competition Bureau Canada (2024). Public consultation on Competition Act’s new greenwashing provisions.

CFA Institute. (2008). Environmental, Social, and Governance Factors at Listed Companies: A Manual for Investors.

Dreisbach, G., & Jurczyk, V. (2022). The role of objective and subjective effort costs in voluntary task choice. Psychological Research, 86(5), 1366-1381.

El Ghoul, S., and A. Karoui. (2021). What’s in a (green) name? the consequences of greening fund names on fund flows, turnover, and performance.

International Financial Reporting Standards (2023). IFRS S1 General Requirements for Disclosure of Sustainability-related Financial Information.

Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada (2021). Know-your-client and suitability determination for retail clients. & IIROC. (2021). Product Due Diligence and Know-Your-Product.

Leibenstein, H. (1950). Bandwagon, snob, and Veblen effects in the theory of consumers' demand. The quarterly journal of economics, 64(2), 183-207.

Leuthesser, L. et al. (1995). Brand equity: the halo effect measure. European journal of marketing.

Malhotra, N. K. (1984). Information and sensory overload. Information and sensory overload in psychology and marketing. Psychology & Marketing, 1(3 - 4), 9-21.

Morningstar (2024). Canadian Investors Stuck with ESG in 2023.

National Instrument 31-103 Registration Requirements, Exemptions and Ongoing Registrant Obligations and Companion Policy to NI 31-103 CP Registration Requirements, Exemptions and Ongoing Registrant Obligations.

Ontario Securities Commission (2020). Investor Experience Research Study.

PRI (2022), What is responsible investment?

PRI (2023), Definitions for responsible investment approaches.

Responsible Investment Association. (2021), 2021 RIA Investor Opinion Survey.

Riedl, A., & Smeets, P. (2017). Why do investors hold socially responsible mutual funds?. The Journal of Finance, 72(6), 2505-2550.

Slovic, P. et al. (2007). The affect heuristic. European journal of operational research, 177(3), 1333-1352.

State Street Global Advisors (2019), The ESG data challenge.