Intelligence artificielle et l’investissement de détail: Cas d’usage et recherche expérimentale

Résumé

Résumé

La récente augmentation de la diffusion de l’intelligence artificielle (IA) et de ses applications offre de nouvelles possibilités, mais aussi de nouveaux risques potentiels pour les particuliers qui investissent. C’est pourquoi les organismes de réglementation des valeurs mobilières s’efforcent de comprendre, de prioriser et de remédier aux préjudices potentiels pour les investisseurs, tout en continuant de favoriser l’innovation.

Les résultats de recherche présentés dans ce rapport ont été élaborés par la Commission des valeurs mobilières de l’Ontario (CVMO) en collaboration avec la Behavioral Insights Team dans le cadre de l’approche fondée sur des données probantes de la CVMO en matière d’initiatives réglementaires et éducatives. Nos résultats proviennent de deux volets de recherche. Nous avons d’abord effectué une revue de la littérature et une analyse de l’environnement des plateformes d’investissement afin de comprendre les principaux cas d’utilisation des systèmes d’IA destinés aux investisseurs particuliers. Nous avons ensuite utilisé les résultats de cette recherche pour concevoir et mettre en œuvre une expérience de science comportementale visant à déterminer comment la source d’une suggestion d’investissement — IA, humain ou un mélange des deux — influe sur la mesure dans laquelle les investisseurs suivent cette suggestion.

Sur la base de l’analyse documentaire et de l’analyse de l’environnement réalisées dans le cadre de notre premier volet de recherche, nous avons identifié trois grands cas d’utilisation de l’IA spécifiques aux investisseurs particuliers :

- Aide à la décision : Les systèmes d’IA qui fournissent des recommandations ou des conseils pour guider les décisions d’investissement des investisseurs particuliers.[1]

- Automatisation : Systèmes d’IA qui automatisent la gestion de portefeuilles ou de fonds (par exemple, ETF) pour les investisseurs particuliers.

- Escroqueries et fraudes Systèmes d’IA qui facilitent les escroqueries et les fraudes ciblant les investisseurs particuliers, ainsi que les fraudes profitant de la « mode » de l’IA.

Dans ces cas d’usage, nous avons identifié plusieurs avantages et risques majeurs liés à l’adoption et à l’utilisation des systèmes d’IA par les investisseurs particuliers, dont les suivants.

Avantages :

- Réduction des coûts : Les systèmes d’IA peuvent réduire le coût des conseils personnalisés et de la gestion de portefeuille, créant de cette façon une valeur considérable pour les investisseurs particuliers.[2]

- Accès aux conseils : Des systèmes d’IA plus sophistiqués et plus correctement réglementés peuvent offrir un accès accru aux conseils financiers aux investisseurs particuliers, notamment à ceux qui ne peuvent accéder à des conseils par les canaux traditionnels.

- Prise de décision améliorée : Des outils d’IA peuvent être développés afin de guider la prise de décision des investisseurs dans des domaines clés, comme la diversification des portefeuilles et la gestion des risques, ainsi que des outils pour aider les investisseurs à identifier les escroqueries financières.[3]

- Performance améliorée : Les recherches existantes ont montré que les systèmes d’IA peuvent prédire avec plus de précision les variations des bénéfices et générer des stratégies d’échanges commerciaux plus rentables que les analystes humains.[4]

Risques

- Biais : En règle générale, les modèles d’IA sont soumis aux préjugés et aux hypothèses des humains qui les développent. À ce titre, ils peuvent accroître les résultats inadéquats, même lorsque cela n’est pas la fonction prévue du système.

- Comportement grégaire : La concentration des outils d’IA parmi quelques fournisseurs peut induire un comportement grégaire, une convergence des stratégies d’investissement et des réactions en chaîne qui exacerbent la volatilité lors des chocs sur le marché.

- Qualité des données : Si un modèle d’IA repose sur des données de mauvaise qualité, alors les résultats, qu’il s’agisse de conseils, de recommandations ou autres, seront aussi de mauvaise qualité.

- Gouvernance et éthique : La nature de « boîte noire » des systèmes d’IA et les limites en matière de confidentialité et de transparence des données suscitent des inquiétudes quant à la question de déterminer clairement qui est responsable dans les cas où les systèmes d’IA produisent des résultats négatifs pour les investisseurs.

Notre deuxième volet de recherche consistait à réaliser un essai contrôlé randomisé (ERC) en ligne. Nous avons vérifié dans quelle mesure des Canadiens ont suivi une suggestion concernant la façon d’investir un montant hypothétique de 20 000 $ dans trois types d’actifs : actions, titres à revenu fixe et liquidités. Nous avons utilisé une variété d’origines de la suggestion d’investissement : un fournisseur de services financiers humains, un outil d’investissement basé sur l’IA ou un fournisseur de services financiers humains utilisant un outil d’IA (c’est-à-dire une approche « hybride »). Nous avons également utilisé comme variable le fait que la suggestion d’investissements d’actif était jugée judicieuse ou non afin de déterminer si les Canadiens pouvaient discerner la qualité des suggestions en fonction de leur origine. Le tableau 1 présente les différentes variantes de suggestions d’investissement que nous avons testées.

Tableau 1 : Suggestions d’investissement

| Human | IA[5] | Hybride | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sain d’esprit | Humain sain d’esprit | IA sain d’esprit | Hybride sain d’esprit |

| Pas sain d’esprit | Humain pas sain d’esprit | AI pas sain d’esprit | Hybride pas sain d’esprit |

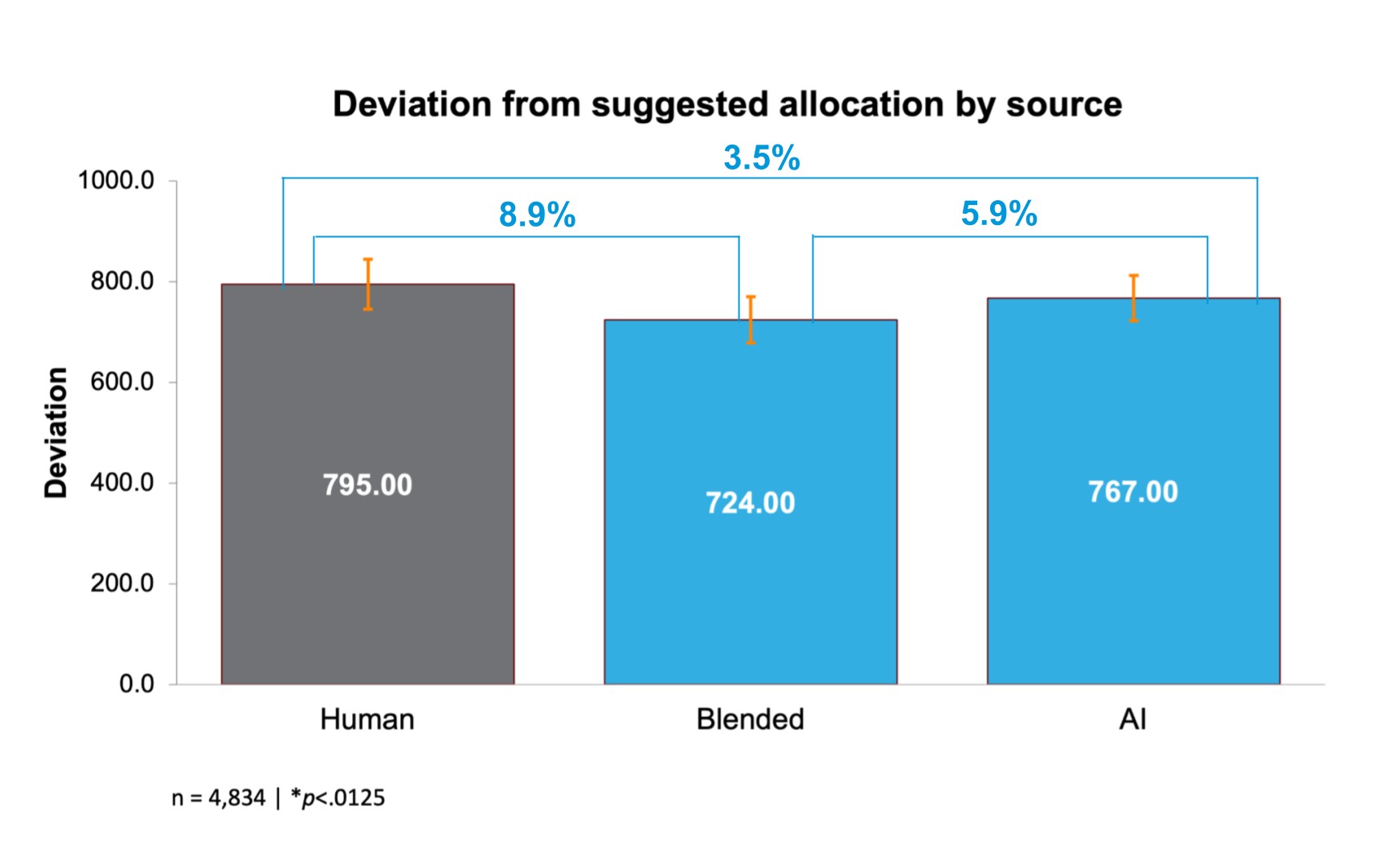

Dans cette expérience, nous avons constaté que les personnes ayant reçu une suggestion d’investissement d’un humain utilisant un outil d’IA (c’est-à-dire un conseiller « hybride ») se conformaient davantage à ladite suggestion. L’écart de leur allocation d’investissement était de 9 % inférieur à celui des personnes qui avaient reçu la suggestion d’une source humaine, et de 6 % inférieur à celui des personnes qui avaient reçu la suggestion d’un outil d’IA. Cependant, ces résultats doivent être interprétés avec prudence. Même s’il y avait des différences moyennes dans la manière dont les groupes investissaient leurs fonds, ces différences n’étaient pas suffisamment importantes pour répondre à nos critères statistiques rigoureux (c’est-à-dire qu’elles n’étaient pas statistiquement significatives). En conséquence, il n’est pas possible d’affirmer que ces résultats indiquent un effet réel, car ils pourraient être dus au hasard. En d’autres termes, ces résultats peuvent être valables, mais nous ne pouvons en être certains sans répétitions de l’expérience.

Dans cette optique, les résultats de notre expérience présentent plusieurs implications clés. Nos données contribuent à combler une lacune importante dans la recherche, dans la mesure où une grande partie des travaux existants ont comparé les différences de confiance dans les conseils financiers provenant d’outils d’IA, ou de prestataires humains uniquement. Notre expérience va au-delà de la confiance déclarée en se concentrant sur le comportement (bien que dans un environnement simulé) en réponse aux suggestions d’investissement provenant de diverses sources. En outre, l’ajout de la condition « hybride » nous a permis de développer une première compréhension de la manière dont les investisseurs réagissent aux suggestions provenant d’un futur état potentiel du conseil en investissement, soit une source « hybride ». Enfin, nos données suggèrent que les Canadiens font confiance aux suggestions d’investissement générées par les systèmes d’IA, car nous n’avons observé aucune différence matérielle dans l’adhésion entre les conditions humaines et celles de l’IA. Cela souligne la nécessité de garantir de façon permanente que les systèmes d’IA fournissant des conseils et des recommandations en investissement soient basés sur des données impartiales et de haute qualité, et qu’à terme, ils améliorent l’expérience des investisseurs particuliers.

[1] Au Canada, la réglementation interdit aux entreprises d’utiliser l’IA pour fournir des conseils ou des recommandations sans surveillance humaine ;ce cas d’usage a été observé dans les autres juridictions.

[2] Banerjee, P. (2 juin 2024). L’IA surpasse les humains en matière d’analyse financière, mais sa véritable valeur réside dans l’amélioration du comportement des investisseurs. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/investing/personal — finance/household-finances/article-ai-outperforms-humans-in-financial-analysis-but-its-true-value-lies-in/

[3] Ibid.

[4] Kim, A., Muhn, M. et Nikolaev, VV (2024). Analyse des états financiers à l’aide de grands modèles de langage. Chicago Booth Research Paper Forthcoming, Fama-Miller Working Paper. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4835311

[5] Le paysage réglementaire au Canada ne permet pas de fournir des recommandations aux investisseurs sans surveillance humaine, et ce, peu importe la technologie utilisée. Notre expérience visait à fournir une indication du comportement des investisseurs devant des suggestions d’investissement provenant de différentes sources en ayant ce contexte réglementaire à l’esprit.

Introduction

Introduction

There has been a significant increase in the scale and breadth of artificial intelligence (AI) systems in recent years, including within the retail investing space. While these technologies hold promise for retail investors, regulators internationally are alert to the risks they pose to investor outcomes. In this context, the Ontario Securities Commission (OSC) collaborated with the Behavioural Insights Team (BIT) to provide a research-based overview of:

- The current use cases of AI within the context of retail investing – and any associated benefits and risks for retail investors.

- The effects of AI systems on investor attitudes, behaviours, and decision-making.

To address these areas, we implemented a mixed-methods research approach with two research streams:

- A literature review and environmental scan of investor-facing AI systems in Canada and abroad to identify the current use cases of AI that are retail investor-facing.

- A behavioural science experiment to determine how the source of an investment suggestion — AI, human, or a blend of the two — impacts the extent to which investors follow that suggestion.

Our report is structured as follows. We first present use cases of AI in retail investing that we have identified. We then present the methodology and results of our behavioural science experiment.

Use Cases

Use Cases

An artificial intelligence (AI) system “…is a machine-based system that, for explicit or implicit objectives, infers, from the input it receives, how to generate outputs such as predictions, content, recommendations, or decisions that can influence physical or virtual environments. Different AI systems vary in their levels of autonomy and adaptiveness after deployment.”[6] The massive growth of available data and computing power has provided ideal conditions to foster advancements in the use of AI across various industries, especially within the financial sector.[7]

AI systems have begun to proliferate in the securities industry with certain applications targeted to retail investors. If responsibly implemented, these applications have the potential to benefit retail investors. For example, they could reduce the cost of personalized advice and portfolio management. However, the use of AI within the retail investing space also brings new risks and uncertainties, including systemic implications:

- Explainability: AI models are often described as “black boxes” because the process by which they reach decisions is unclear.[8]

- Data Quality: AI systems are only as good as the data upon which they are based. If systems are based on corrupted, biased, incomplete, or otherwise poor data, investor protection could be compromised.

- Bias: AI models are generally subject to the biases and assumptions of the humans who developed them.[9] As such, they may accelerate or heighten unfair outcomes, even where this is not the algorithm’s intended function.[10]

- Herding: The concentration of AI tools among a few providers may induce herding behaviour, convergence of investment strategies, and chain reactions that exacerbate volatility during shocks.[11] In other words, if markets are driven by similar AI models, volatility could increase dramatically to the point of financial system contagions.[12]

- Market Competition: Large firms with big budgets and greater technological capabilities are generally at a greater advantage than smaller firms in developing AI tools – which could reduce the competitive landscape.

- Principal-Agent Risks: AI applications developed and used by firms to advise or provide other support to retail investors could be developed to prioritize the interests of the firm rather than their clients. This potential risk is exacerbated by the high complexity and low explainability of AI tools. In the US, the SEC has recently proposed rules to address this risk.[13]

- Scalability: Due to the scalability of AI technologies and the potential for platforms that leverage this technology to reach a broad audience at rapid speed, any harm resulting from the use of this technology could affect investors on a broader scale than previously possible.[14]

- Governance: The rapid development of AI systems may result in poorly defined accountability within organizations. Organizations should have clear roles and responsibilities and a well-defined risk appetite related to the development of AI capabilities.[15]

- Ethics: Like any technology, AI can be manipulated to cause harm. Organizations should maintain transparency, both internally and externally, through disclosure on how they ensure high ethical standards for the development and usage of their AI systems.[16]

In this report, we outline three areas where AI is being used in certain jurisdictions within the retail investing space, namely, Canada, the United States, the EU, and the UK: decision support, automation, and scams and fraud.[17]

Decision Support

We classify decision support as AI applications that provide recommendations or advice to guide investment decisions.[18] This includes applications that provide advice directly to retail investors and those that help individual registrants provide advice to their retail investor clients.[19] Decision support may relate to individual securities transactions or overall investment strategy / portfolio management. Our behavioural science experiment (below) explores this use case in the context of investment allocation decisions.

Platforms for self-directed retail investors have started offering “AI analysts” as an add-on feature to support investor decision-making. For example, a US-based firm has partnered with a US-based fintech platform to leverage AI in analyzing large datasets to provide insight into a range of global assets for users. These applications appear to be intended to provide self-directed investors with relevant insights, information, and data to inform their investment decisions.

Standalone AI tools have also been developed to directly support investors. For example, one US-based platform allows investors to enter the details of their financial status such as their debt, real estate, and investment accounts to receive advice on whether their investments match their financial goals and risk tolerance. A new CHATGPT plug-in by the same company allows investors to have conversations with an AI-powered chatbot that can make similar suggestions, simply by reading a copy and paste of one’s investing statements. Another US-based company operates as a standalone website to provide investors with AI-driven tools for identifying patterns and trends in the stock market. The company’s first product was a website which featured AI tools to help retail investors gauge how well their portfolio was diversified.

Automation

We define automation as AI applications that automate portfolio and/or fund (e.g., ETF) management for retail investors. Unlike decision support, these AI applications require minimal user input, making investment decisions for investors instead of providing advice and letting the investor decide. There are three key types of AI applications that automate decisions: robo-advisor platforms using AI, AI-driven funds (e.g., ETFs), and standalone AI platforms offering portfolio management.

Robo-advisers have been using algorithms to automate investing for Canadian retail investors since 2014. In Canada, securities regulators require human oversight over investment decisions generated by algorithms.[20] Other countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia, appear to permit similar robo-advising platforms to manage client funds with little or no involvement from a human advisor.[21] Within these other markets, there is an emerging trend of robo-advisors using AI. For example, one US-based platform is reportedly using AI to automatically rebalance portfolios and perform tax-loss harvesting for users.

AI-powered exchange-traded funds (ETFs) use AI to identify patterns and trends in the market to identify investment opportunities and manage risk. For example, the US-based WIZ Bull-Rider Bear-Fighter Index was described as using AI to analyze market conditions and automatically shift holdings from “momentum leaders” in bull markets to “defensive holdings” during bear markets.[22] The fund has since been liquidated.[23] Other fund examples include Amplify AI Powered Equity ETF (AIEQ), VanEck Social Sentiment ETF (BUZZ), WisdomTree International AI Enhanced Value Fund (AIVI), and Qraft AI-Enhanced U.S. Large Cap Momentum ETF (AMOM).[24]

Finally, some standalone AI platforms offer automated portfolio management. For example, a US-based platform claimed to use AI and human insight to anticipate market movements and automatically manage, rebalance, and trade different account holdings for self-directed investors.

Scams and Fraud

AI systems can also be used to enhance scams and fraud targeting retail investors, as well as generate scams capitalizing on the “buzz” of AI.

AI is “turbocharging” a wide range of existing fraud and scams. In the past two years, there has been nearly a ten-fold increase in the amount of money lost to investment-related scams reported to the Canadian Anti-Fraud Centre (an increase from $33 million in 2020 to $305 million in 2022).[25] One factor contributing to this increase is that scammers are using AI to produce fraudulent materials more quickly and increase the reach and effectiveness of written scams. Large language models (LLMs) increase scam incidence in three ways. First, they lower the barrier to entry by reducing the amount of time and effort required to conduct the scam. Second, LLMs increase the sophistication of the generated materials as typical errors such as poor grammar and typographical errors are much less frequent.[26] Finally, through “hyper-personalization,” LLMs can improve the persuasiveness of communications. For example, scammers may use AI to replicate email styles of known associates (e.g., family).[27] Beyond applications in email or other written formats, AI has also been used to generate “deepfakes” that deceive investors by impersonating key messengers. A deepfake is a video or voice clip that digitally manipulates someone’s likeness.[28] Deepfake scams have replicated the faces of celebrities, loved ones in distress, government officials, or fictitious CEOs to steal money or personal information from investors.[29],[30] Deepfakes can also be used to bypass voice biometric security systems needed to access investment accounts by cloning investors’ voices.[31] In the future, we may even see instances of deepfakes of investors’ own faces to access investment accounts that use face biometrics.[32],[33]

While many fraudsters use AI to enhance scams, other fraudsters are simply capitalizing on the hype of AI to falsely promise high investment returns. For example, YieldTrust.ai illegally solicited investments on an application that claimed to use “quantum AI” to generate unrealistically high profits. The platform claimed that new investors could expect to earn returns of up to 2.2% per day.[34] These scams tend to advertise “quantum AI” and use social media and influencers to generate hype around their product. For example, the Canadian Securities Administrators issued a 2022 alert for a company called ‘QuantumAI’, flagging that it is not registered in Ontario to engage in the business of trading securities.[35]

[6] OECD. (2023). Updates to the OECD’s definition of an AI system explained. https://oecd.ai/en/wonk/ai-system-definition-update

[7] European Securities and Markets Authority. (2023). Artificial Intelligence in EU Securities Markets. https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/library/ESMA50-164-6247-AI_in_securities_markets.pdf

[8] Wall, L. D. (2018). Some financial regulatory implications of artificial intelligence. Journal of Economics and Business, 100, 55-63.

[9] Waschuk, G., & Hamilton, S. (2022). AI in the Canadian Financial Services Industry. https://www.mccarthy.ca/en/insights/blogs/techlex/ai-canadian-financial-services-industry

[10] European Securities and Markets Authority. (2023). Artificial Intelligence in EU Securities Markets. https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/library/ESMA50-164-6247-AI_in_securities_markets.pdf

[11] Ibid.

[12] Financial Times. (2023). Gary Gensler urges regulators to tame AI risks to financial stability. https://www.ft.com/content/8227636f-e819-443a-aeba-c8237f0ec1ac

[13] Proposed Rule, Conflicts of Interest Associated with the Use of Predictive Data Analytics by Broker-Dealers and Investment Advisers, Exchange Act Release No. 97990, Advisers Act Release No. 6353, File No. S7-12-23 (July 26, 2023) (“Data Analytics Proposal”). https://www.sec.gov/files/rules/proposed/2023/34-97990.pdf

[14] Ibid.

[15] Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (2023). Financial Industry Forum on Artificial Intelligence: A Canadian Perspective on Responsible AI. https://www.osfi-bsif.gc.ca/en/about-osfi/reports-publications/financial-industry-forum-artificial-intelligence-canadian-perspective-responsible-ai

[16] Ibid.

[17] We exclude use cases which do not have unique characteristics or implications specific to retail investing (e.g., chat bots).

[18] In Canada, regulations do not permit firms to provide advice or recommendations without human oversight; this use case was observed in the other jurisdictions.

[19] Individual registrants include financial advisors, investment advisors, and other individuals providing investment advice without any AI assistance.

[20] CSA Staff Notice 31-342 - Guidance for Portfolio Managers Regarding Online Advice. https://www.osc.ca/en/securities-law/instruments-rules-policies/3/31-342/csa-staff-notice-31-342-guidance-portfolio-managers-regarding-online-advice

[21] Ibid.

[22] WIZ. (2023, September 30). Merlyn.AI Bull-Rider Bear-Fighter ETF.https://alphaarchitect.com/wp-content/uploads/compliance/etf/factsheets/WIZ_Factsheet.pdf

[23] Merlyn AI Bull-Rider Bear-Fighter ETF. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/quote/WIZ:US

[24] Royal, James. (2024, May 6). 4 AI-powered ETFs: Pros and cons of AI stockpicking funds. Bankrate. https://www.bankrate.com/investing/ai-powered-etfs-pros-cons/

[25] Berkow, J. (2023, September 7). Securities regulators ramp up use of investor alerts to flag concerns. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/article-canadian-securities-regulators-investor-alerts/

[26] Fowler, B. (2023, February 16). It’s Scary Easy to Use ChatGPT to Write Phishing Emails. CNET. https://www.cnet.com/tech/services-and-software/its-scary-easy-to-use-chatgpt-to-write-phishing-emails/

[27] Wawanesa Insurance. (2023, July 6). New Scams with AI & Modern Technology. Wawanesa Insurance. https://www.wawanesa.com/us/blog/new-scams-with-ai-modern-technology

[28] Chang, E. (2023, March 24). Fraudster’s New Trick Uses AI Voice Cloning to Scam People. The Street. https://www.thestreet.com/technology/fraudsters-new-trick-uses-ai-voice-cloning-to-scam-people

[29] Choudhary, A. (2023, June 23). AI: The Next Frontier for Fraudsters. ACFE Insights. https://www.acfeinsights.com/acfe-insights/2023/6/23/ai-the-next-frontier-for-fraudstersnbsp

[30] Department of Financial Protection & Innovation. (2023, May 24). AI Investment Scams are Here, and You’re the Target! Official website of the State of California. https://dfpi.ca.gov/2023/04/18/ai-investment-scams/#:~:text=The%20DFPI%20has%20recently%20noticed,to%2Dbe%2Dtrue%20profits.

[31] Telephone Services. TD. https://www.td.com/ca/products-services/investing/td-direct-investing/trading-platforms/voice-print-system-privacy-policy.jsp

[32] Global Times. (2023, June 26). China’s legislature to enhance law enforcement against ‘deepfake’ scam. Global Times. https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202306/1293172.shtml?utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=B2B+Newsletter+-+July+2023+-+1

[33] Kalaydin, P. & Kereibayev, O. (2023, August 4). Bypassing Facial Recognition - How to Detect Deepfakes and Other Fraud. The Sumsuber. https://sumsub.com/blog/learn-how-fraudsters-can-bypass-your-facial-biometrics/

[34] Texas State Securities Board. (2023, April 4). State Regulators Stop Fraudulent Artificial Intelligence Investment Scheme. Texas State Securities Board. https://www.ssb.texas.gov/news-publications/state-regulators-stop-fraudulent-artificial-intelligence-investment-scheme

[35] Canadian Securities Administrators. (2022, May 20). Quantum AI aka QuantumAI. Investor Alerts. https://www.securities-administrators.ca/investor-alerts/quantum-ai-aka-quantumai/

Experimental Research

Experimental Research

This section describes the methodology and findings of an experiment testing how the source of investment suggestions — AI, human, or a blend of the two (‘blended’) — impacts adherence to that suggestion. We also tested whether any differences in adherence depend on the soundness of the suggestion. The experiment was conducted online with a panel of Canadian adults in a simulated trading environment.

We conducted the experiment in two waves. As described further in the results section, in the first wave of the experiment, the recommended cash allocation in the “unsound” condition was objectively very high (20%) but it was also the level that participants naturally gravitated toward, regardless of the suggestion they received. This meant that adherence overall was higher in the “unsound” condition, which in turn limited our ability to assess the interaction effects between soundness of the advice and source of that advice.

To address this issue, we collected a second wave of data approximately three months later. In this second wave, we kept the suggested cash allocation consistent between the sound and unsound conditions and varied the equity and fixed income suggestions to reflect the soundness of the suggestion. We also collected data for a “control” group that did not receive any suggestion. We did this to understand how participants would allocate their funds in the absence of an investment suggestion, testing our hypothesis about the underlying preference for a larger cash allocation.

We conducted two waves of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) to examine how the source and soundness of an asset allocation suggestion influenced the extent to which participants adhere to the suggestion.

Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs)

A randomized controlled trial (RCT) is an experimental approach designed to measure the effectiveness of a particular intervention or set of interventions. The effect of a particular intervention is measured by comparing the group of participants who receive the intervention (treatment group) to the group that does not receive the intervention (control group). An RCT can be run with multiple variations of the intervention (treatment groups), all of which can be compared to the control group. RCTs are considered to be the gold standard in experimentation primarily because they establish a causal link between the interventions and the outcomes observed. RCTs also have the advantage of minimizing bias by randomly assigning participants to different experiment groups so that any differences between participants are distributed across conditions.

Our experiment consisted of a three (source type: human, AI, vs human with AI) by two (soundness of advice: sound vs unsound) factorial design. The investment suggestion pertained to how participants should allocate their fictitious funds ($20,000) to equities, fixed income, and cash. In addition to adherence, we measured self-reported trust in the suggestion and deviation from the suggestion by asset class (e.g., equities).

Participants in the experiment were told they would be investing $20,000 across equities, fixed income, and cash, and were asked to do so as if it were their own money and situation. Participants that were not in the control condition were introduced to WealthTogether, a fictitious financial services firm, to help them decide how to allocate their funds. They were then introduced to one of three WealthTogether financial services providers: (1) A person named Alex; (2) a person named Alex that is using an AI tool to inform their suggestions; or (3) an AI tool named Kai. Screenshots of the introduction for each provider are presented in Appendix B.

Participants then completed a brief investor questionnaire that sought to broadly assess their risk profile. The questionnaire was designed based on common industry practices and consisted of three questions related to investment horizon, risk tolerance, and age. Based on responses to the questionnaire, participants were grouped into one of three investor profiles – conservative, balanced, or growth – using the schema in Appendix A. The purpose of the questionnaire was to make the experience feel more realistic and personally relevant to participants. We also wanted the investment suggestion to feel more relevant and legitimate to ensure the findings generalize to the real world context outside of this experiment.

Based on the investor profile that participants were assigned to, they received a suggestion (from the financial services provider) on how to allocate their funds across equities, fixed income, and cash. The suggestion was either:

- Sound: A suggestion that is in line with widely accepted financial principles for allocating one’s investable assets based on the investor’s profile (e.g., allocating a significant portion of one’s funds to fixed income for a low-risk investor); or

- Unsound: A suggestion that clearly goes against widely accepted financial principles for allocating one’s investable assets based on the investor’s profile (e.g., allocating a significant portion of one’s funds to equities for a low-risk investor).

Table 2 outlines the specific asset allocation suggestions the participants received, depending on their experimental condition:

Table 2: Asset Allocation Suggestions

| Investor Profile | Equities | Fixed Income | Cash |

Sound Suggestion | Growth | 80% | 15% | 5% |

Balanced | 60% | 35% | 5% | |

Conservative | 20% | 75% | 5% | |

Unsound Suggestion Wave 1 | Growth | 50% | 30% | 20% |

Balanced | 30% | 50% | 20% | |

Conservative | 65% | 15% | 20% | |

Unsound Suggestion Wave 2 | Growth | 15% | 80% | 5% |

Balanced | 20% | 75% | 5% | |

Conservative | 75% | 20% | 5% | |

Unadvised Control | Growth |

No suggestion provided | ||

Balanced | ||||

Conservative | ||||

After participants received the suggestion, they allocated the full $20,000 across any combination of equities, fixed income, and cash. They were not required to follow the suggestion they were given, but rather, were given autonomy to decide how they allocate their funds across the three assets.

After the allocation activity, participants answered questions related to their trust in the investment suggestion they were provided, their experience using AI tools, and demographic information. Table 3 summarizes the conditions that participants were assigned to.

Table 3: Experiment Conditions

| Condition[36] | Description |

|---|---|

| Treatment A: Sound Human Suggestion | Participants received a sound suggestion from a human financial services provider. |

| Treatment B: Sound Blended Suggestion | Participants received a sound suggestion from a human financial services provider that used an AI tool to support their suggestion. |

| Treatment C: Sound AI Suggestion | Participants received a sound suggestion from an AI tool. |

| Treatment D: Unsound Human Suggestion | Participants received an unsound suggestion from a human financial services provider. |

| Treatment E: Unsound Blended Suggestion | Participants received an unsound suggestion from a human financial services provider that used an AI tool to support their suggestion. |

| Treatment F: Unsound AI Suggestion | Participants received an unsound suggestion from an AI tool. |

| Treatment G: Unadvised Control (Wave 2) | Participants did not receive any suggestion for how to allocate their funds. |

In the first wave of our experiment, we collected data for all six treatments groups. In the second wave, we collected new data for only the three unsound groups and a control group. In our analysis, we compared the unsound treatment groups data from our second wave to data from the sound treatment groups from the first wave. Only a few months had passed between the two waves and there were no major events in capital markets (e.g., a market crash) or investment advisory services (e.g., major scandals) during that period.

During the second wave of data collection, we also collected data for an additional “unadvised” control group that completed the same asset allocation activity but were not provided with any suggestion for how to allocate their funds. This group still completed the investor questionnaire and were told what type of investor the questionnaire classified them as (conservative, balanced, or growth).

The total sample across both waves of the experiment consisted of 7,771 Canadian residents aged 18 years and older. The samples were similar across both waves of data collection based on the proportion of participants who were current investors, their gender, age, and completion of the experiment on a mobile device. Across both waves, 60% of the sample consisted of current investors (40% non-investors). Our sample was well balanced on gender (51% non-male) and age (median of 43 years).

[36] All financial services professionals were fictitious and from the same (fictitious) financial services provider, WealthTogether.

Primary Results: Deviation From Suggested Asset Allocation

Our primary analysis focused on how closely participants adhered to the suggested allocation of their funds across the three asset classes (equities, fixed income, cash). We were primarily interested in how the source of the suggestion – human, AI, or a blend of the two – influenced adherence to the suggestion. We analyzed adherence to the suggestion by looking at the differences between the suggested allocation and the chosen allocation across each of the three types of assets. Our main finding was that participants adhered most closely to the suggestion provided by a blend of human and AI sources (“blended”) although this finding needs to be interpreted with caution as described below. Our results indicate that Canadians may have an explicit or implicit view that the benefits of either human or AI investment advice can be maximized by combining the two. We provide a discussion of these results and other findings from the experiment below.

Source of Suggestion

As shown in Figure 1 below (Wave 2 data for unsound conditions), participants who received a suggestion from the blended source deviated 8.9% less from the suggested allocation than participants who received the suggestion from the human source.[37] This is equivalent to participants in the blended source groups adhering to the suggested allocation by $404 more than those in the human source groups (out of a total of $20,000). However, this result was not statistically significant at our more conservative statistical threshold, and should be interpreted with caution.[38]

Statistical Significance

Statistical significance is a measure used to determine whether the results of an experiment (such as differences between groups) are likely due to a real effect of an intervention or simply due to chance. Typically, a result is considered statistically significant if the probability (p-value) of observing such results when they do not actually exist is below a predetermined threshold, often set at 0.05. In our experiment, we used a more stringent p-value threshold of 0.0125, following commonly accepted statistical practices to account for multiple comparisons that were conducted between groups.

Participants who received a suggestion from the AI source deviated slightly less (-3.5%) from the suggested allocation than participants who received the suggestion from the human source, and slightly more (+5.9%) than participants who received the suggestion from the blended source. These differences were, however, not statistically significant. The absence of a significant difference between these conditions may indicate that Canadian investors do not have an obvious aversion to receiving advice from an AI system in comparison to a human advisor.

The results are consistent with the Wave 1 data, in which participants who received a suggestion from the blended source deviated 11.0% less from the suggested allocation than participants who received the suggestion from the human source.

Figure 1: Deviation from suggested investment (n=4,834). Participants adhered most closely to blended, but differences are not statistically significant.

This finding addresses an important gap in the existing evidence base. Previous research has primarily compared differences in trust in financial advice from AI tools or human advisors only. The addition of the blended advice arm allowed us to develop an understanding of how investors perceive the quality and trustworthiness of advice provided by a hybrid source (i.e., a human using an AI tool). Investors appear to prefer this type of advice, as demonstrated by their increased adherence to the allocation suggestion within these conditions. By examining hypothetical asset allocation rather than a self-reported level of trust, we obtain a more accurate and behaviour-oriented measure of the impact of AI, human, and blended sources of advice on investor behaviour.

While other literature suggests that investors are less trusting of advice provided by AI compared to human advisors, we observed similar levels of adherence between these sources. There are compelling and relevant explanations for this finding. First, the literature suggests that people feel personally connected to AI that uses their data to provide recommendations.[39] Second, increased explanation of AI algorithms (e.g., what data is being used in the algorithms) was found to increase adoption of AI tools.[40] Both of these factors were present in our experiment: participants were told they needed to fill out an investor questionnaire for the tool to provide a more personalized investment suggestion, and they were also told what data was used in the AI algorithm. Finally, and more broadly, sentiment toward AI is positively correlated with familiarity,[41] and the recent explosion in the popularity and salience of LLMs may be shifting attitudes.

Soundness of Suggestion

Data from Wave 2 of our experiment showed that participants who received a “sound” suggestion deviated 74% less from the suggested allocation than those who received an “unsound” suggestion, a statistically significant difference. This result was consistent with our hypothesis, given that sound suggestions followed widely accepted principles for investing.

Canadians have a strong preference to invest in cash

During the first wave of our experiment, participants who received the “unsound” suggestion deviated 14.5% less from the suggested asset allocation than those who received a “sound” suggestion. This result was surprising, and we explored the data further. We developed a hypothesis that this surprising result was due to one specific asset category—cash. During the first wave, across all conditions (both sound and unsound), participants allocated approximately 20% of their funds to cash, on average. This level of allocation happened to be exactly what was suggested in the unsound conditions, whereas the sound conditions suggested 5%. We chose 5% for the sound conditions to match industry norms, and 20% for unsound because it was far outside those standards. We speculated that adherence was higher in the unsound conditions purely because we picked an unsound cash allocation that aligned with pre-existing participant preferences. This meant that we could not generate the hoped-for insight on how the soundness of advice interacted with the effect of the source of the advice.

Our hypothesis was confirmed by the second wave data. The “unadvised” control group allocated about 20% to cash, on average. When we updated the suggested cash allocation for “unsound” groups to 5%, we identified the expected pattern – there was 74% higher adherence in the sound conditions compared to the unsound ones, and we were able to conduct the analysis as planned.

While we did not set out to study Canadians’ asset allocation tendencies, we think the data we obtained is important. Simply put, under widely accepted standards for asset allocation, the high preference for cash (around 20%) will reduce retail investors’ long-term returns. This is especially important given that the cash allocations in this experiment were presented as non-interest earning (e.g., chequing account). We believe this significant preference for cash may be explained in part by the equity premium puzzle,[42][43] or other prominent investing biases, including extreme aversion bias[44] and confirmation bias.[45] Our data suggests critical policy and educational priorities. For example, educational efforts might focus on appropriate levels of risk-taking, keeping in mind both excessive risk-seeking and excessive risk-aversion.

Secondary Results: Interaction Effects

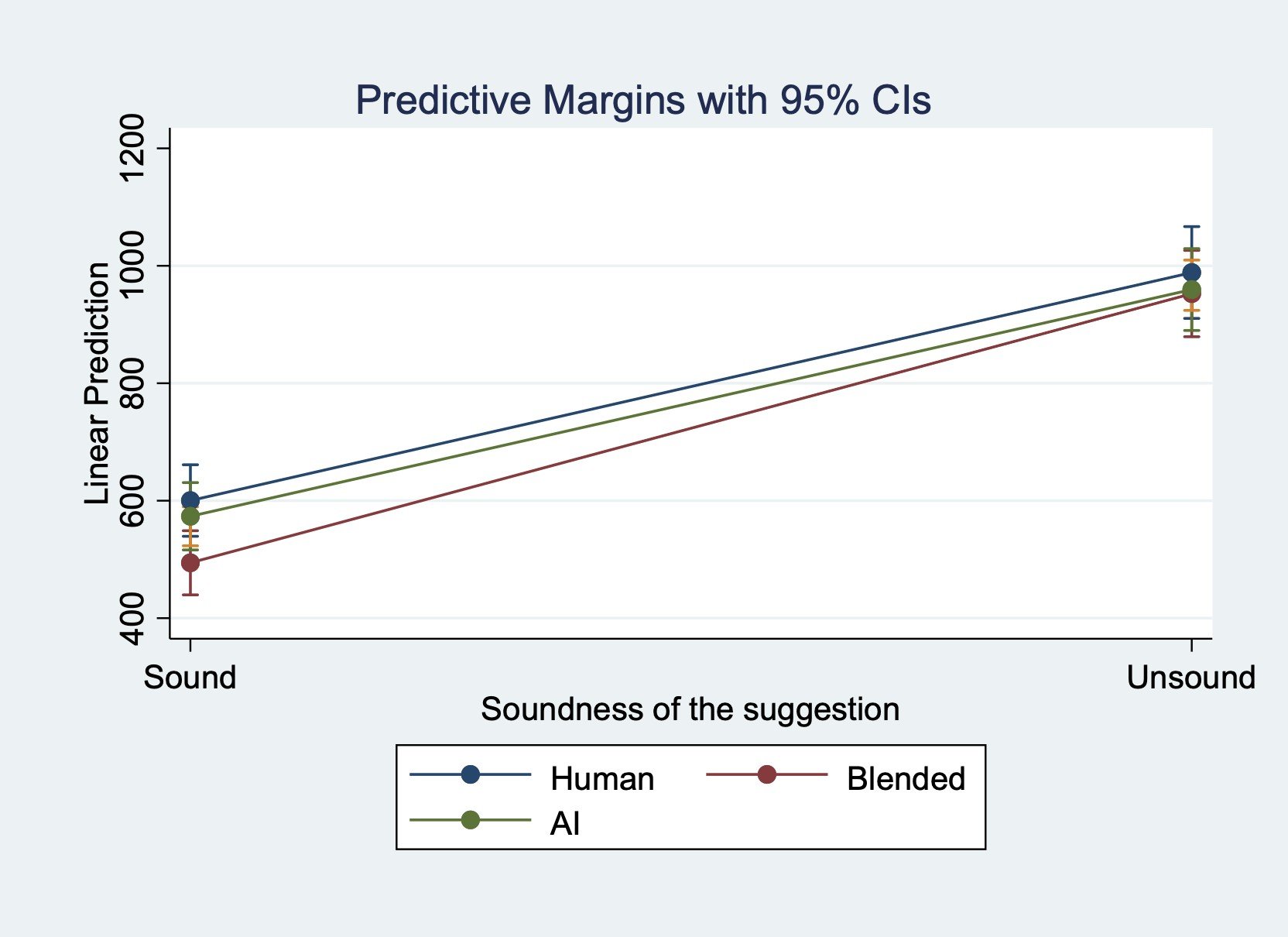

Next, we examined whether suggestion soundness and the source interact in some way to affect adherence to a suggestion. As shown in Figure 2, we did not identify the presence of a statistically significant interaction effect. These results suggest that adherence to investment suggestions from the sources we tested (human, AI, and blended) does not depend on the soundness of the suggestion, but rather, that the two relationships are independent.

Figure 2: Interaction effects (n=4,834). No significant interaction between source and soundness of suggestion to effect adherence.

Exploratory Results

In addition to deviation from the suggested asset allocation, we collected additional data to better understand investor behaviour and sentiment with respect to AI.

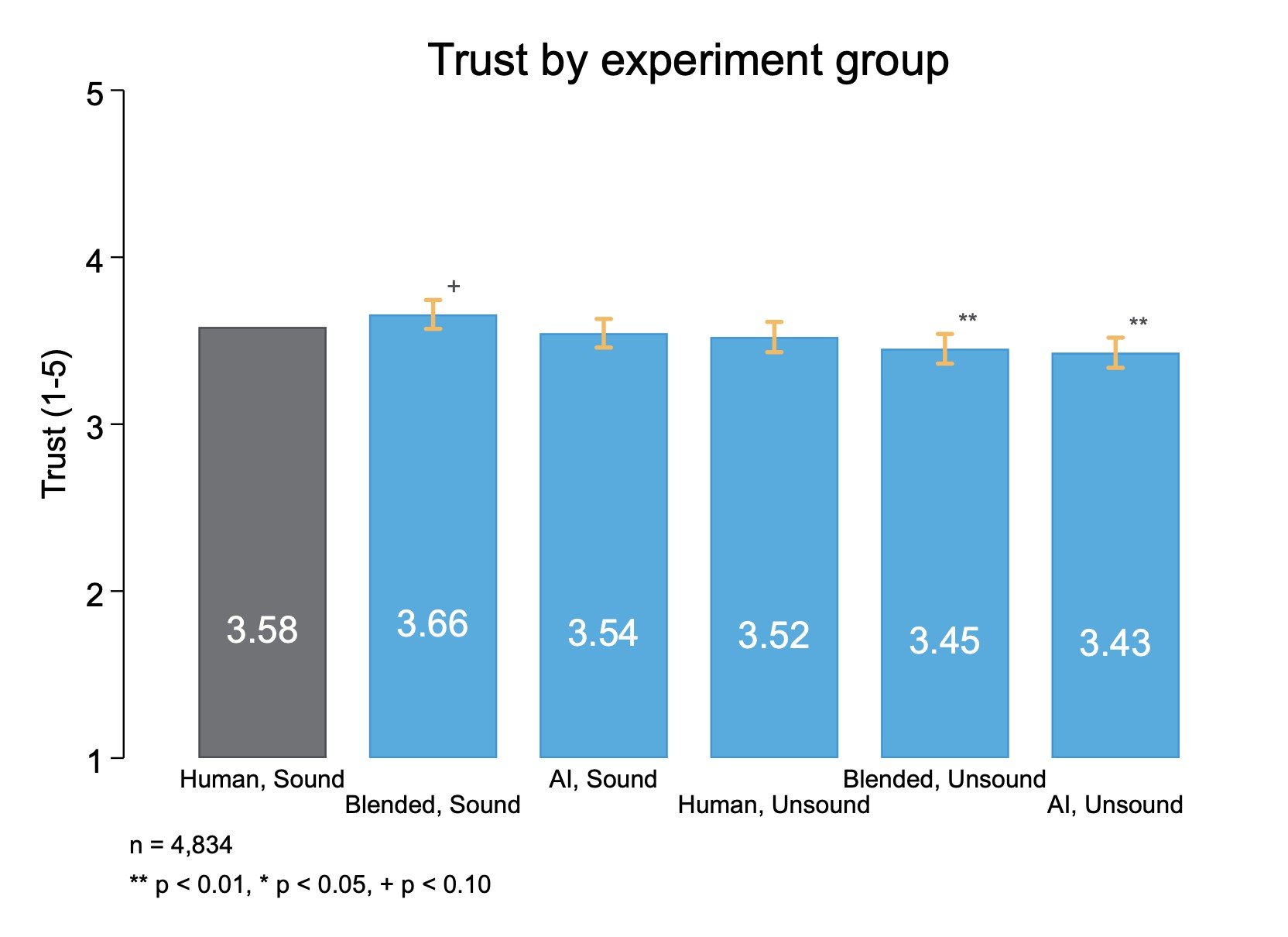

Trust

We explored how participants’ trust in the investment suggestion they received may influence their adherence to the suggestion. As shown in Figure 3 (Wave 2 data) trust in the suggested allocation was moderately high across all participants, despite the substantial deviations from the suggested allocations in the unsound conditions. We observed small differences in trust in the suggestion across treatment groups.[46] Interestingly, trust was lower among the unsound blended and AI arms, but not unsound human arm, compared to the sound human arm, despite participants deviating to a similar degree across all sources of the unsound suggestions. These results suggest an imperfect relationship between trust in the suggestion and adherence to the suggestion, showing the importance of behavioural data to understand benefits and risks related to various sources of financial advice.[47]

Figure 3: Trust in investment suggestion (n=4,834). Small differences in trust observed between certain groups.

Asset Allocation by Soundness of Suggestion

We also explored how participants allocated their funds across each asset when provided with a sound suggestion, an unsound suggestion, or no suggestion at all.

Table 4 below presents the percentage of funds allocated to equities, fixed income, and cash, across the sound, unsound, and no suggestion groups from the second wave of the experiment. Across all groups, participants allocated similar amounts to cash (approximately 19%), and differed their allocations to equities and fixed income. Across all groups, there appears to be a degree of “extreme aversion” bias, with participants wanting to even out their allocations across the asset classes available. In addition to a preference for cash and extreme aversion bias, this data indicates the influence of advice – even unsound advice – in shifting allocation preferences.

Table 4: Asset Allocations

Investor Profile | Equities | Fixed Income | Cash | |

| Sound Suggestion | Growth | 63% | 23% | 14% |

Balanced | 47% | 35% | 19% | |

Conservative | 28% | 50% | 23% | |

| Unsound Suggestion | Growth | 50% | 37% | 13% |

Balanced | 35% | 46% | 18% | |

Conservative | 45% | 34% | 21% | |

| No Suggestion | Growth | 57% | 27% | 16% |

Balanced | 41% | 37% | 22% | |

Conservative | 35% | 39% | 25% |

Experience With AI Applications

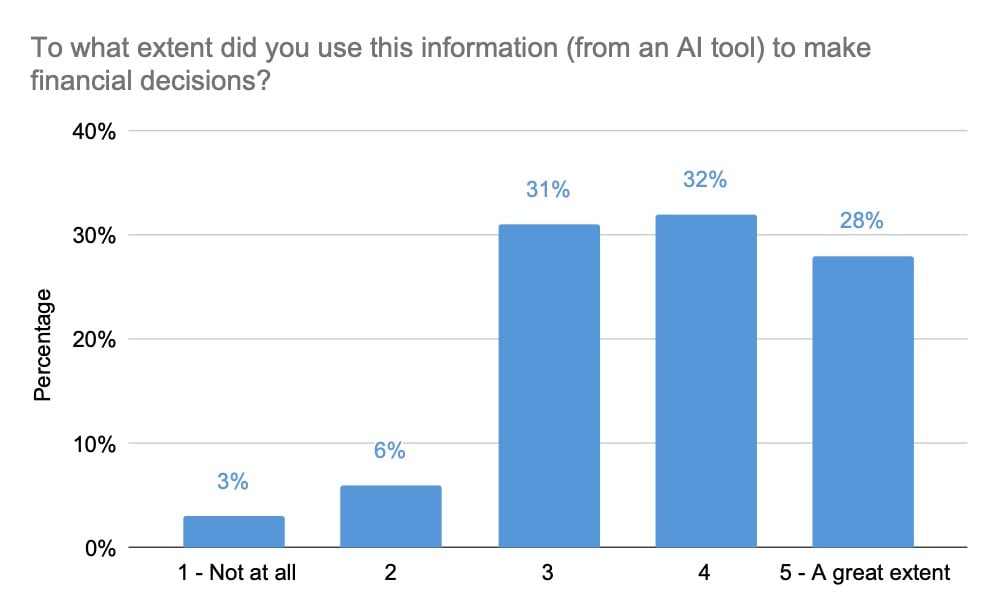

A third of our total sample reported using an AI application (e.g., ChatGPT) in the last year. Among that group, 29% had used the application to access financial or investment-related information, advice, or recommendations. The vast majority of those participants reported having acted on the information, advice, or recommendations they received from the AI tool (Figure 4). Among the sample of participants who reported using AI tools to access financial information, there appears to be substantial trust in the information provided. Over 90% of participants who engaged with an AI tool reported that they used the outputs to make financial decisions to at least a moderate extent.

These findings present a number of key implications. First, a significant portion of Canadians (29%) are already using AI to access financial information, advice, and recommendations, despite the fact that not all of these applications are registered with securities regulators. This figure will likely rise moving forward as AI tools are increasingly scaled. Second, the vast majority (90%) of those engaging with AI applications are using the information to inform their financial decisions to at least a moderate extent. This reinforces the need for a regulatory framework that ensures that the outputs of AI models are accurate and appropriate for retail investors. It also indicates that Canadian investors are not merely interested in AI-generated financial information, but in some cases, may be relying on that information to inform investing decisions.

Figure 4: Usage of AI for financial decisions (n=864). Majority of participants report having acted on financial information provided by AI.

The results from our experiment should be interpreted in light of the fact that it took place in a controlled, online environment. One particular limitation is that participants did not have a relationship with the human or “blended” financial service providers, as they might in the real world. In contrast, the AI condition was likely more representative of how an investor would interact with an AI tool in a real-life setting. Overall, we hypothesize that in a real-world setting, adherence to investment advice may be higher than what we observed in the human and blended groups because of the trust and engagement produced by working with a human advisor. Further research to investigate and validate this hypothesis would be valuable.

[37] In the Figure, the y-axis or “deviation” is the measure of the sum of the squares of the differences between the actual asset allocation (0%-100%) and the suggested asset allocation. It is not a meaningful value in its own right, so what is important is the relative difference between the groups.

[38] This result is trending towards but was not statistically significant (p=0.037) when using the multiple-comparison adjusted p-value of 0.0125. We used this more conservative threshold for statistical significance rather than the conventional p=0.05 to account for making four comparisons in our primary analysis.

[39]Huang, B., & Philp, M. (2021). When AI-based services fail: examining the effect of the self-AI connection on willingness to share negative word-of-mouth after service failures. The Service Industries Journal, 41(13-14), 877-899.

[40]David, D.B., Resheff, Y.S., & Tron, T. (2021). Explainable AI and Adoption of Financial Algorithmic Advisors: An Experimental Study. Proceedings of the 2021 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society.

[41] Horowitz, M. C., & Kahn, L. (2021). What influences attitudes about artificial intelligence adoption: Evidence from US local officials. Plos one, 16(10), e0257732.

[42] Mehra, R., & Prescott, E. C. (1985). The equity premium: A puzzle. Journal of monetary Economics, 15(2), 145-161.

[43] Well-known phenomenon describing underinvestment by retail investors in equities compared to fixed income (Treasury Bills in particular). This underinvestment arises from biases in risk analysis and risk aversion that would also explain underinvestment in equities and fixed income compared to cash.

[44] We see evidence that participants in both the sound and unsound conditions moved toward a more even allocation across the three asset categories.

[45] It appears that participants were more likely to follow the suggestion that may have aligned with their own beliefs about an appropriate cash allocation.

[46] The largest difference, a 2.8% difference, was observed between the unsound AI group and the sound human group and is statistically significant (p<0.05).

[47] These results were consistent with the results from the first wave of data, where trust was similar across all treatment groups, and different patterns were observed between the self-reported trust in the suggestion and adherence to the suggestion.

Conclusion

Conclusion

The applications of artificial intelligence within the securities industry have grown rapidly, with many targeted to retail investors. AI systems offer clear potential to both benefit and harm retail investors. The potential harm to investors is made more pronounced by the scalability of these applications (i.e., the potential to reach a broad audience at rapid speed). The goal of this research was to support stakeholders in understanding and responding to the rapid acceleration of the use of AI within the retail investing space.

The research was conducted in two phases. First, we conducted desk research. This phase included a scan and synthesis of relevant behavioural science literature, examining investors’ attitudes, perceptions, and behaviours related to AI. We also conducted a review of investing platforms and investor-facing AI tools to understand how AI is being used on investing platforms. Our desk research revealed that the existing evidence base on how these tools impact investors is limited, and may not be highly generalizable in the future, given how recent the rapid evolution of AI has been.

From our desk research phase, we identified three broad use cases of AI within the retail investing space:

- Decision Support: AI systems that provide recommendations or advice to guide retail investor investment decisions.

- Automation: AI systems that automate portfolio and/or fund (e.g., ETF) management for retail investors.

- Scams and Fraud: AI systems that either facilitate or mitigate scams and fraud targeting retail investors, as well as scams capitalizing on the “buzz” of AI.

In the second phase of this research, we built an online investment simulation to test investors’ uptake of investment suggestions provided by a human, AI tool, or combination of the two (i.e., a human using an AI support tool). The experiment generated several important insights. We found that participants adhered to an investment suggestion most closely when it was provided by a blend of human and AI sources. However, this difference did not meet our more stringent statistical thresholds, and as such, we cannot be certain that it is not due to chance. That said, this finding adds to existing research on AI and retail investing, as the current literature does not examine “blended” advice. Importantly, we found no discernible difference in adherence to investment suggestions provided by a human or AI tool, indicating that Canadian investors may not have a clear aversion to receiving investment advice from an AI system.

Our research also identified several risks associated with the use of AI within the retail investing space that could lead AI tools to provide investors with advice that is not relevant, appropriate, or accurate. Like human suggestions, AI and blended sources of suggestions had a material impact on the asset allocation decisions of participants, even when that advice was unsound. This underlines the ongoing need to understand the provision of investment recommendations from AI systems, especially given the observed openness among Canadians to AI-informed advice. In particular, there is a need to ensure that algorithms are based on high quality data, that factors contributing to bias are proactively addressed, and that these applications prioritize the best interests of investors rather than the firms who develop them.

Regulators are already proposing approaches to address these risks. For example, in the US, the SEC proposed a new rule that would require investment firms to eliminate or neutralize the effect of any conflict of interest resulting from the use of predictive data analytics and AI that places the interests of the firm ahead of the interests of investors.[48] More broadly, industry regulators and stakeholders should seek to leverage data collected by investing platforms and investor-facing AI tools to investigate the extent to which these tools are resulting in positive or negative outcomes for investors.

The results of our experiment suggest one other critical policy and education implication; investors appear to have a strong bias to holding more cash in their investment portfolios than most financial experts recommend. This finding suggests that excessive cash allocations should be a focus of educational efforts, with this focus potentially broadened to appropriate risk-taking when investing.

This research also underscores several positive impacts that AI tools may have on investor behaviours. For example, tools could be created to support financial inclusion through increased access to more affordable investment advice. We also see a significant opportunity for AI to be used by stakeholders to improve the detection of fraud and scams.

AI presents a range of potential benefits and risks for retail investors. As this technology continues to advance in capabilities and applications, more research will be needed to support capital markets stakeholders in better understanding the implications for retail investors. This report provides important findings and insights for stakeholders in an increasingly complex environment.

[48] U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. (2023). SEC Proposes New Requirements to Address Risks to Investors From Conflicts of Interest Associated With the Use of Predictiv Data Analytics by Broker-Dealers and Investment Advisers. Press Release. https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2023-140

Authors & Appendices

Authors

Ontario Securities Commission:

Patrick Di Fonzo

Senior Advisor, Behavioural Insights

[email protected]

Matthew Kan

Senior Advisor, Behavioural Insights

[email protected]

Marian Passmore

Senior Legal Counsel, Investor Office

[email protected]

Meera Paleja

Program Head, Behavioural Insights

[email protected]

Kevin Fine

Senior Vice President, Thought Leadership

[email protected]

Behavioural Insights Team (BIT):

Laura Callender

Senior Advisor

[email protected]

Riona Carriaga

Associate Advisor

[email protected]

Sasha Tregebov

Director

[email protected]

Appendices

Table 1: Questions, Responses, and Classifications

Question | Classification: Conservative | Classification: Balanced | Classification: Growth | |

| Time Horizon | When do you think you may need to access the money you are investing? | <5 years | 5-10 years | >10 years |

| Risk Preference | Which for these statements best describes you attitudes towards risk when making investment decisions: | I am conservative; I try to minimize risk altogether or am willing to accept a small amount of risk | I am willing to accept a moderate level of risk and tolerate moderate losses to achieve potentially higher returns. | I am aggressive and typically take on significant risk. I can tolerate large losses for the potential of achieving higher returns. |

| Age (open response) | How old are you? | 60+ years | 40-59 years | 18-39 years |

Table 2: Response Scoring Schema

Conservative | Balanced | Growth | |

| Scoring Schema |

|

|

|

[49] “Low”, “medium”, and “high” refer to the risk profile indicated by each of the three questions.

Human Conditions

AI Conditions

Blended Conditions

Click for Image: Investor Questionnaire

Click for Image: Investment Allocation

NOTE: The Investment Allocation image shows the display for participants in the sound human condition. Participants in the other conditions (sound AI, sound blended, unsound human, unsound AI, unsound blended) were shown a suggestion with the relevant soundness and source. Participants in the unadvised control group (Wave 2) did not receive any suggestion.

Banerjee, P. (2024, June 2). AI outperforms humans in financial analysis, but its true value lies in improving investor behavior. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/investing/personal -finance/household-finances/article-ai-outperforms-humans-in-financial-analysis-but-its-true-value-lies-in/

Berkow, J. (2023, September 7). Securities regulators ramp up use of investor alerts to flag concerns. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/article-canadian-securities-regulators-investor-alerts/

Canadian Securities Administrators. (2022, May 20). Quantum AI aka QuantumAI. Investor Alerts. https://www.securities-administrators.ca/investor-alerts/quantum-ai-aka-quantumai/

Chang, E. (2023, March 24). Fraudster’s New Trick Uses AI Voice Cloning to Scam People. The Street. https://www.thestreet.com/technology/fraudsters-new-trick-uses-ai-voice-cloning-to-scam-people

Choudhary, A. (2023, June 23). AI: The Next Frontier for Fraudsters. ACFE Insights. https://www.acfeinsights.com/acfe-insights/2023/6/23/ai-the-next-frontier-for-fraudstersnbsp

CSA Staff Notice 31-342 - Guidance for Portfolio Managers Regarding Online Advice. https://www.osc.ca/en/securities-law/instruments-rules-policies/3/31-342/csa-staff-notice-31-342-guidance-portfolio-managers-regarding-online-advice

David, D.B., Resheff, Y.S., & Tron, T. (2021). Explainable AI and Adoption of Financial Algorithmic Advisors: An Experimental Study. Proceedings of the 2021 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society.

Department of Financial Protection & Innovation. (2023, May 24). AI Investment Scams are Here, and You’re the Target! Official website of the State of California. https://dfpi.ca.gov/2023/04/18/ai-investment-scams/#:~:text=The%20DFPI%20has%20recently%20noticed,to%2Dbe%2Dtrue%20profits.

European Securities and Markets Authority. (2023). Artificial Intelligence in EU Securities Markets. https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/library/ESMA50-164-6247-AI_in_securities_markets.pdf

Financial Times. (2023). Gary Gensler urges regulators to tame AI risks to financial stability. https://www.ft.com/content/8227636f-e819-443a-aeba-c8237f0ec1ac

Fowler, B. (2023, February 16). It’s Scary Easy to Use ChatGPT to Write Phishing Emails. CNET. https://www.cnet.com/tech/services-and-software/its-scary-easy-to-use-chatgpt-to-write-phishing-emails/

Global Times. (2023, June 26). China’s legislature to enhance law enforcement against ‘deepfake’ scam. Global Times. https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202306/1293172.shtml?utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=B2B+Newsletter+-+July+2023+-+1

Horowitz, M. C., & Kahn, L. (2021). What influences attitudes about artificial intelligence adoption: Evidence from US local officials. Plos one, 16(10), e0257732.

Huang, B., & Philp, M. (2021). When AI-based services fail: examining the effect of the self-AI connection on willingness to share negative word-of-mouth after service failures. The Service Industries Journal, 41(13-14), 877-899.

Kalaydin, P. & Kereibayev, O. (2023, August 4). Bypassing Facial Recognition - How to Detect Deepfakes and Other Fraud. The Sumsuber. https://sumsub.com/blog/learn-how-fraudsters-can-bypass-your-facial-biometrics/

Kim, A., Muhn, M., & Nikolaev, V. V. (2024). Financial statement analysis with large language models. Chicago Booth Research Paper Forthcoming, Fama-Miller Working Paper. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4835311

Mehra, R., & Prescott, E. C. (1985). The equity premium: A puzzle. Journal of monetary Economics, 15(2), 145-161.

Merlyn AI Bull-Rider Bear-Fighter ETF. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/quote/WIZ:US

OECD. (2023). Updates to the OECD’s definition of an AI system explained. https://oecd.ai/en/wonk/ai-system-definition-update

Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (2023). Financial Industry Forum on Artificial Intelligence: A Canadian Perspective on Responsible AI. https://www.osfi-bsif.gc.ca/en/about-osfi/reports-publications/financial-industry-forum-artificial-intelligence-canadian-perspective-responsible-ai

Proposed Rule, Conflicts of Interest Associated with the Use of Predictive Data Analytics by Broker-Dealers and Investment Advisers, Exchange Act Release No. 97990, Advisers Act Release No. 6353, File No. S7-12-23 (July 26, 2023) (“Data Analytics Proposal”). https://www.sec.gov/files/rules/proposed/2023/34-97990.pdf

Royal, James. (2024, May 6). 4 AI-powered ETFs: Pros and cons of AI stockpicking funds. Bankrate. https://www.bankrate.com/investing/ai-powered-etfs-pros-cons/

Telephone Services. TD. https://www.td.com/ca/products-services/investing/td-direct-investing/trading-platforms/voice-print-system-privacy-policy.jsp

Texas State Securities Board. (2023, April 4). State Regulators Stop Fraudulent Artificial Intelligence Investment Scheme. Texas State Securities Board. https://www.ssb.texas.gov/news-publications/state-regulators-stop-fraudulent-artificial-intelligence-investment-scheme

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. (2023). SEC Proposes New Requirements to Address Risks to Investors From Conflicts of Interest Associated With the Use of Predictiv Data Aanalytics by Broker-Dealers and Investment Advisers. Press Release. https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2023-140

Wall, L. D. (2018). Some financial regulatory implications of artificial intelligence. Journal of Economics and Business, 100, 55-63.

Waschuk, G., & Hamilton, S. (2022). AI in the Canadian Financial Services Industry. https://www.mccarthy.ca/en/insights/blogs/techlex/ai-canadian-financial-services-industry

Wawanesa Insurance. (2023, July 6). New Scams with AI & Modern Technology. Wawanesa Insurance. https://www.wawanesa.com/us/blog/new-scams-with-ai-modern-technology

WIZ. (2023, September 30). Merlyn.AI Bull-Rider Bear-Fighter ETF.https://alphaarchitect.com/wp-content/uploads/compliance/etf/factsheets/WIZ_Factsheet.pdf